John was born in 1932, in Highfield House, at what was later to become Nottingham University, where his father, Hugh Stewart, was the Principal. His father tragically died when John was only one year old and his sister was three.

At the onset of World War Two the family moved, firstly to Dovedale in Derbyshire, then to Great Malvern in Worcestershire, where John and Margaret, his sister, went to school, before moving again to Criccieth on the north Wales coast where John began a very happy time at school at Deudraeth Castle which had been converted into a small school, close to Portmerion. After the war they moved to Canford Cliffs on the Dorset coast, and from here John went on to Stowe which he loved.

His two years of National Service included a one year Russian course, in which Russian linguists in all three services (army, navy, air force) were being trained as interpreters and translators. He subsequently graduated with an MA in History from Trinity College, Cambridge, and his passion for these subjects was to lead him later to his career path.

After settling in London John took a job with Operation Britain as personal assistant to its director which he hugely enjoyed. He then worked for PR firm Bennett Associates for 2½ years before leaving to follow his Russian interests. He reflected a few years ago that his first interest in Russia was because his father had been there before the revolution and this was then reinforced by John’s half-brother Michael being in Archangel in Russia for a year during the second world war. He said what focused his attention was that he discovered there was going to be a British Trade Fair in Moscow in about 1960 and he got a job there as an interpreter.

It was around this time in London that John met his future wife, Penelope, a professional solo cellist, at a mutual friend’s party in about 1958. He was tentative as to whether two careers within a marriage would work and to investigate interviewed several well-known couples, including the actors Cecil Day-Lewis and his wife, Jill Balcon, parents of Daniel Day-Lewis. His multi-page article with his photographs of the couples was published in Tatler, and forms part of a wide-ranging archive the family has of works he was to go on to produce. His fears were unfounded or it was the advice he received which held him in good stead, as he remained devoted to Penelope and she to him for over 50 years, with two (also devoted) children.

Despite having fallen for Penelope, in 1961 after a lot of planning for what had become an increasingly ambitious trip, John drove a Mini across Russia with his friend David Ashwanden, and described this extraordinary journey in his book Across the Russias. A few years ago he reflected, “That Russian trip in 1961, apart from marrying Penelope, was I think the highlight of my life.”

With his extensive travels and photography, in part with his mother and sister, he began to get his photographs published, and started writing Across the Russias, his first book. He had first had a camera when his brother Michael sent him one from Berlin where he was stationed after the war. John commented that nobody really taught him about photography and that he just learnt on his own, although he had previously joined a correspondence course. He remained freelance from then on, giving photo-illustrated lectures all over the UK, mostly through the Maurice-Frost Lecture Agency, many of them being in the north of England and he would arrive back in London on the last train late at night. Many of his lectures and conference papers he also presented in Ireland, France, USA, Canada, Israel, Poland and Siberia.

His office off the Strand, near Charing Cross in central London provided much historic and architectural interest, which he imparted also to his children, before he eventually moved to work from his home in Highgate, London. The home was a buzz of activity with the two careers in the marriage. Alongside his many articles, often with his own photographs, published in The Times, The Guardian, The Sunday Times, New York Sunday Times, Country Life, Tatler, and more, John set up his own picture library with global requests for his images coming in via fax, email and phone at all hours. More recently he assigned his images to be accessible through the Mary Evans Picture Library, among others. The John Massey Stewart Picture Library consists of his own 5,000 black & white, 11,000 colour photographs and images of Russia past and present, approximately 10,000 colour photographs of some 30 countries, and approximately 8,000 images of classical composers’ portraits, statues, homes, and gravestones.

John also wrote a number of books, on environmental issues in eastern Europe and the former Soviet republics: The Soviet environment: problems, policies and politics; and more recently a biography of an artist and his extraordinary travels in the 19th century also across Russia and into Kazakhstan, Thomas, Lucy and Alatau: The Atkinsons Adventures in Siberia and the Kazakh Steppe. When he passed away, aged almost 91, he was still working on another three books and had ideas and research collated for others.

John performed a number of notable consultancy roles during his career, including as Specialist Adviser to the House of Commons Environment Committee enquiry into UK environmental aid programmes to Central and Eastern Europe including the Former Soviet Union in 1995. He was also part of a high level delegation to Russia that included David Bellamy. Additionally, he worked for the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) in Moscow (1992), West Siberia (1992), and Lake Baikal region (World Bank project) (1994) and was a member of the organising committee for the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Sustainable Development of the Lake Baikal Region in 1994.

He ran programmes and projects for many years as founder in the 1990s of the Conservation Foundation’s London Initiative on the Russian Environment - an international initiative to help facilitate, network and coordinate Western projects and programmes on Russia’s environment. His largest audience was one of 2000 people at a football stadium for a conference in Russia. His most intrepid undertaking perhaps was that of learning to scuba dive in his mid-50s with the express purpose of diving in Lake Baikal, which always held a special place for him - an ambition he successfully accomplished.

John certainly led a very interesting life: “Never a dull moment” was a phrase frequently uttered at home, with names of organisations such as the Scott Polar Research Institute routinely featured in family conversations, and it was simply accepted that he knew many fascinating people, such as a Russian scientific expert on polar bears and a mammoth expert. Another was a wonderful half-Sioux American lady with the Sioux name of Brown Duck, who became a good family friend. And there was the story of the Russian princess he had met on the Tube in London and helped her to find her way - he was initially surprised at the very intrigued reaction of his son to this story and they both then laughed about how for him it was apparently just one of many intriguing anecdotes in his life!

John had a wide range of interests with remarkable knowledge, with his particular interest in Siberia and the Russian Far East, the Russian environment and Russian history, but he was also greatly interested in nature generally and wider environmental issues. His professional fellowships and memberships included over decades the Royal Geographical Society, the Linnean Society, the Royal Institute for International Affairs, the Royal Society for Asian Affairs (where he was honorary librarian for 11 years), and the British Association for Slavonic and East European Studies, among others. Until very recently he was still attending all of these when possible.

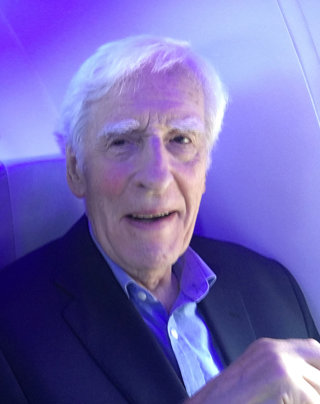

The large number of very interesting and diverse friends he had, who he greatly enjoyed entertaining and introducing to one another, reflect the wide range of interests that he so keenly followed. He has typically been described by them as very kind, gentle, thoughtful, distinguished, a gentleman, caring, and having a wonderful sense of humour and warmth of spirit. One of his friends recently wrote, “His enthusiasm and that twinkle in his eye always brightened our day”. John often tried to make sure people were at ease and felt comfortable. Several people have commented on the substantial positive impact he made on their lives.

John’s infinite sense of curiosity, quest for exploration and research of things, history and people’s stories, as well as their well-being, and an inimitable twinkle in his eye made him who he was.

In early 2023, after recovering from COVID-19 he went into an excellent residential home in Cheltenham, near to his son, as he needed to recuperate for the 2+ hours journey back to London and life back home again. This turned into a longer stay and his two children visited him regularly. He loved his excursions in the local area including to Gloucester Cathedral and Tewkesbury Abbey and fantastic views for miles from a hilltop of the surrounding landscapes including the distant Malvern hills and of Malvern itself where he had lived for a while as a child.

John passed away on 26 October 2023 with his daughter and son at his side.

To quote Nottingham University that had so much relevance for him: “Today, we bid farewell to a valued friend, but the memory of John's important work and his inimitable character will forever be etched in our hearts and minds.”

He will be greatly missed.

Words by John's children.