January 2015

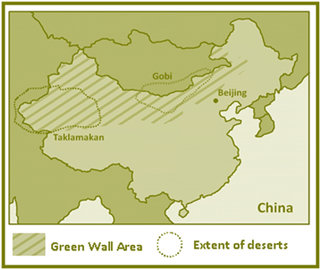

Northern China has a long history of being dry. The Himalayas which run through the mid-west of the country create a rain shadow over the country’s northern border with Mongolia, which prevents rainfall reaching the region and annual precipitation figures of 100 to 250mm compared to around 1500mm for mainland China. The result is the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts which have a combined size of over 1.6 million km2.

These deserts are rapidly expanding. Around 3600km2 of China’s grassland is lost to the Gobi desert every year as well as 2000km2 of top soil. Not only does this make agriculture in these regions very challenging but this desertification has the effect of sweeping dust across the country and into the east coast cities. This dust, alongside industrial pollution, has been blamed for creating dangerously high levels of air pollution at in Beijing, as it can trap particulates at ground level.

The ‘Great Green Wall’

The ‘Great Green Wall’ or, more formally, the Three-North Shelterbelt Forest Programme has been one method the Chinese authorities have deployed to slow down desertification in this region. The ‘wall’ is actually strips and patches of trees planted in vast swathes across the north of China. These trees act as wind breaks to the dust storms that frequently blow across the area from the Gobi and Taklamakan deserts; storms that break up soil and reduce the area’s farming capacity. Trees are also used to stabilise sand dunes in some areas and gravel stages are placed in order to encourage the reestablishment of a soil crust.

The planting of these trees started in 1978 and is due to be completed in 2050. At that time it is estimated the programme’s tree belt will stretch for 4500km, encompass 100 billion trees and will be the world’s largest ecological engineering project. The ‘wall’ is already the world’s largest artificial forest.

How successful has it been?

The ‘Great Green Wall’ programme has not been without its critics. Geographers have been nervous about citing the ‘wall’ as a success, noting that the reduced intensity of dust storms could be explained by small increases in rainfall which would naturally dampen the effect of the former. However, new research from the Research Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resource Research in Beijing suggests that the positive effects of the ‘wall’ are warranted.

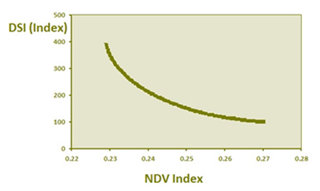

Professor Minghong Tan, the study’s chief researcher found that the reduction in the intensity of dust storms can be attributed to the wholesale planting of trees in northern China (Tan and Li, 2015). Using an index which combines data on visibility during a dust storm with the length of the storm itself known as DSI (Dust Storm Intensity) (Tan et al, 2014), and comparing it with a second index; the Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) which combines data for leaf area, photosynthesis and primary productivity (Piao et al, 2011), Tan was able to show a direct correlation between the increase in vegetation growth and a reduction in DSI.

He and his colleagues have found that the further one recorded data away from the ‘wall’ the more significant rainfall became as a factor towards reducing DSI. This indicts that the vegetation cover had indeed significance in reducing the effects of desertification. Dust storm frequency has decreased continuously since 1971 (Wang et al, 2010) and Tan found that between by 1999 this decrease had amounted to a 81.7 percent drop compared to 1985 levels, something he directly attributes to the ‘Great Green Wall’.

Comparing the pre-planting DSI data with that of today sees significant reductions in the most northerly regions of China, but one cannot claim that the ‘wall’ has had a positive effect on DSI everywhere. In Gansu province, in central north China, the Gobi and Taklamakan deserts are both expanding faster than the ‘wall’ can prevent and are starting to meet and join in this region. In only one region has the DSI increased (South Taklamakan): a region where it was most difficult to plant vegetation due to exceptionally loose geological conditions. These conditions in themselves may explain the increase in dust storms there.

Criticism of the programme

Despite its apparent successes critics of the programme as a whole continue to raise concerns about its lack of sustainability. The biological and ecological integrity of the region is called into question by many academics who are wary of the long term impacts of planting trees in a region where they would not naturally occur (Jiang, 2012) as well as citing the common misconception that trees have a greater power to slow desertification over drought-resistant shrubs and grasses (O’Connor and Ford, 2014). Planting a monoculture of trees (in most cases poplar and willow) in some regions can have a negative effect on wildlife and make the forests more susceptible to diseases. In 2012 the World Bank donated US$80 million to the programme to see the planting of more indigenous mixes of plants in an attempt to reduce this aspect of the ‘wall’.

Planting trees in an arid regions places greater pressure on the already stretched water supplies. In Minqin region, in the central north of the country, precipitation has been too low to replenish aquifers and some ground water levels have dropped by as much as nineteen metres (Gaoming, 2008). There is already evidence that in order to maintain the vegetation cover set out in the plan some trees are being replaced and replanted every three years.

Despite these concerns, the results of this new research could signal a green light for the Great Green Wall of the Sahara and Sahel Initiative (GGWSSI) which is attempting to reduce the effects of desertification in central Africa.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2000) Tackling desertification in the Korqin Sandy Lands through integrated afforestation, FAO Forestry

Gaoming, J. (2008) China’s Green Deserts

Jiang, H. (2012) Great Green Wall (China), in Geall, S. Liu, J. and Pellissery, S. (eds.) China, India, and East and Southeast Asia: Assessing Sustainability (The Encyclopaedia of Sustainability Vol. 7) p174–176.

O’Connor, D. and Ford, J. (2014) Increasing the effectiveness of the ‘Great Green Wall’ as an adaptation to the effects of climate change and desertification in the Sahel, Sustainability 6:10, p7142-7154

Piao, S. Wang, X. Ciasis, P. Zhu, B. Wang, T. and Liu, J. (2011) Changes in satellite derived vegetation growth trend in temperate and boreal Eurasia from 1982-2006, Global Change Biology 17, p3228-3239

Tan, M. Li, X. and Xin, L. (2014) Intensity of dust storms in China from 1980-2007: a new definition, Atmospheric Environment 85, p215-222

Tan, M. and Li, X. (2015) Does the Green Great Wall effectively decrease dust storm intensity in China? Land Use Policy 43, p42-47

Wang, X. Zhang, C. Hasi, E. and Dong, Z. (2010) Has the Three-North Shelterbelt Forest Programme solved the desertification and dust storm problem in arid and semi-arid China, Journal of Arid Environment 74, p13-22

Lesson Ideas

Students could consider how else (other than frequency and size of dust storms) one might measure the success of a project designed to slow the spread of the desert. Students should think about how it can be inherently challenging to find meaningful data in this context.

Through research into the various causes of desertification, students should identify which are true of the Gobi and Taklamakan regions. With this in mind, students can look at alternative management techniques to tackle the increasing spread of the two deserts.

Ask students to compare the mechanisms involved in the Great Green Wall with the potential plan for a Green Wall in the Sahel. Students should think about what part of the processes would have to change and how they could be adapted to suit an African landscape and budget.

Why not read about Africa's Great Green wall?

Key words

Aquifer

An underground geological formation or group of formations that contain water and is a source of ground water for wells and springs.

Aridity

The degree of dryness of a climate in a given location.

Desertification

The process by which land becomes increasingly arid and the desert grows in size and depth.

Drought resistant

Plants that are able to survive in very arid conditions due to a series of adaptations.

Dust storm

A weather event where a strong wind blows dust and sand off the surface of the soil or desert.

Rain shadow

The dry area on the lee side of a mountain which receives little rainfall as a result of the mountains blocking the preceding wet weather system.