It is estimated that more than eight million people in the UK struggle to put food on the table, with over half regularly going a day without eating (Food Foundation, 2016). It is in this landscape that emergency food provision is increasingly visible in the UK. The Trussell Trust oversees 424 food banks in the UK and over 2015-2016 it gave out enough emergency food to feed more than 1.1 million individuals. In her book Hunger Pains (2016) Dr Garthwaite explores the realities of foodbank use under austerity and growing health inequalities.

Your book Hunger Pains explores life inside foodbank Britain. Can you tell me about how foodbanks work?

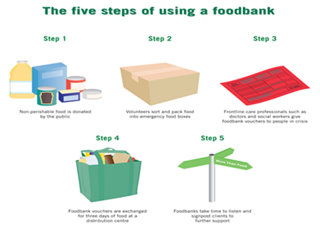

The Trussell Trust runs a network of over 400 foodbanks, giving emergency food and support to people in crisis across the UK. There are five stages involved in the operation of a Trussell Trust foodbank. Firstly, food is donated; secondly, food is sorted and stored; thirdly, people seeking a donation are assessed by frontline professionals; fourthly, vouchers are taken to a foodbank to be redeemed for 3 days of emergency food; and finally, people are signposted to further support through the ‘More Than Food’ programme. Increasingly, Trussell Trust foodbanks are also locating additional services, like debt and welfare advice, within the foodbank itself too. The infographic below shows this in detail:

The five steps of using a foodbank © Chris Orton, Durham University

The research took place in Stockton on Tees; can you tell me more about the area and the people you worked with?

Stockton-on-Tees, in the North East of England, has the highest spatial health inequalities within a single local authority in England both for men and for women. Men living in one of the most deprived parts of the area will live, on average, 17.3 years less than a man living in one of the least deprived areas. For women, the difference is 11.4 years (Public Health England, 2015). I spent time in both of these communities, finding out what it was like to live in a place with such large gaps in life expectancy.

In general, whilst participants from both areas were unaware of the gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas, they showed an understanding of the geographical exclusion between the two localities. For participants in the least deprived area, the idea of inequalities was a vague yet shocking one; for those in the most deprived area, it was felt and lived on a daily basis.

Provision for informal food aid in the UK has existed for many years, but more recently has become a visible part of the social landscape. Why is this?

Historically, we have always had soup kitchens for people who are homeless, but the extent to which provision has grown and expanded so incredibly quickly in recent years is staggering. In 2004 the Trussell Trust ran only two foodbanks. In 2009/10, their foodbanks helped almost 41,000 people. Two years later, with the Coalition government in power, the Trussell Trust issued 128,697 vouchers in 2011/12. In 2014/15, for the first time, over one million emergency food parcels were given out by the Trussell Trust’s network of over 400 foodbanks, an eight fold increase from 2011/12. Today, different forms of emergency food provision have become so much more widespread, with breakfast clubs, pay-as-you-can cafes, soup kitchens, and waste food redistribution all firmly rooted in the fabric of our everyday lives in the UK. There are also people helped by the thousands of independent emergency food providers currently operating in the country; those living in towns where there is no foodbank; people who are too ashamed to seek help; and the large number of people who are coping by eating less and buying cheaper food.

How many people are helped by foodbanks? © Trussell Trust

What sorts of effects can food insecurity have on health in the UK?

Poverty leading to inadequate nutrition is one of the oldest and most serious global health problems. But in 2015, dangerously poor diets are leading to the shocking return of rickets and gout – diseases of the Victorian age that affect bones and joints – according to the UK Faculty of Public Health. One in five family doctors were asked to refer a patient to a foodbank in 2014, with GPs reporting that benefits delays are leaving people without money for food for lengthy periods of time. There are even rare reported cases of people visiting their GP with “sicknesses caused by not eating.”

Many people who used the foodbank had pre-existing health problems which were made worse by their poverty and food insecurity. The latter meant although foodbank users were well aware of the importance and constitution of a healthy diet, they were usually unable to achieve this for financial reasons, constantly having to negotiate their food insecurity. More typically they had to access poor quality, readily available, filling, processed foods. Necessity, not the luxury of choice, means that people were forced to eat food that was cheap, readily available, and would not result in any wastage. Skipping meals led to rapid weight loss, a lack of energy and the worsening of pre-existing ill health, including mental health issues.

It is generally understood that work can offer a route out poverty, but this isn’t always the case. Can you tell me why?

Working families are increasingly turning to foodbanks to make ends meet. Work should offer a reliable route out of poverty. But low pay, high costs of housing, childcare, and transport prevent some people from working or earning more, trapping people in poverty. More than half of people in poverty live in a family where someone is in work. There are 6.7 million working people in the UK who are living in poverty (Joseph Rowntree Foundation 2013), with more than half of people experiencing poverty now living in working households. More than half of households in working poverty (56 per cent) contain a worker paid less than the Living Wage; for the others, the issue is more the number of hours being worked than the amount they're paid. These are jobs that are low paid, low skilled, inflexible, and insecure and contribute to in-work poverty.

Unfortunately, in the UK people are often stigmatised for living in poverty, how can this be addressed?

Media portrayals of poverty are encouraging the idea that foodbank users, and indeed people living in poverty more generally, are in some way to blame for their own situation, creating false distinctions between ‘us’ and ‘them’. This was reflected in the perspectives of the more affluent residents in Stockton-on-Tees who I met throughout the research. For people using the foodbank, this stigmatisation could create a fear so powerful that sometimes it could not be overcome, stopping people from accessing the help they need.

We need to listen to the voices of people using the foodbank so that can we understand who uses them, why, and what it feels like. Maybe then we can start to do something about it. How we express the collective shame that should be felt over the existence of emergency food aid will be key to the future of foodbanks in the UK.

Lesson Ideas

Watch the videos on Paul, Josh, and Sarah stories, create a zine that tells their story and considers:

What brought Marcella, Paul, Josh, and Sarah to the foodbank?

What issues were they experiencing? How were they feeling the effects of poverty?

How did they experience the foodbank, how did it help them?

In which ways has the foodbank assisted in ways beyond providing food?

Individually, research the usual products that are given away as part of a foodbank parcel. Consider the meals that you can create for this, how it would stretch between your own families? Have you noticed foodbanks in your local area, do you feel they are becoming more prevalent?

Taking a map of the UK, using data from the Office of Statistics map the spatial inequalities of life expectancy, health and well-being across the UK – what patterns are emerging?

Links

Will Austerity increase the North South Health Divide? Geography Directions (2015)

Trussell Trust to deliver more emergency food parcels than ever before (2016)

Food bank use could be highest in 12 years, say Trussell Trust. The BBC (2016)

Benefit sanctions forcing people to use food banks, study confirms. The Guardian (2016)

Life on the breadline: benefit cuts are making food banks a permanent fixture. The Guardian (2016)

Reliance on food banks must not become the new norm, say Trussell Trust. The Guardian (2016)

Austerity, welfare reform and the English health divide, Area (2015)

Trussell Trust

Food Foundation

Kayleigh was interviewed in November 2016