What is Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD)?

Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) is endemic in animals in many parts of the world including Asia, Africa, the Middle East and South America. It affects cloven-hoofed animals, in particular cattle, sheep, pigs, goats and deer, causing fever and blisters (predominantly in the mouth and on feet). Other animals that can be infected include llamas and alpacas, and some wild animals including hedgehogs and elephants! Very few human cases of the disease have ever been recorded.

The most serious outbreak of FMD in Britain (and one of the largest in global history) was recorded in 2001. This outbreak involved 2030 cases, spread across the country, and resulted in the culling of six million animals (4.9 million sheep, 0.7 million cattle and 0.4 million pigs), and losses of some £3.1 billion to agriculture and the food chain. Some £2.5 billion was paid by the Government in compensation for slaughtered animals and payments for disposal and clean-up costs. In August/September 2007, eight confirmed cases of FMD were recorded in a localised area in the South East of England.

FMD matters because the outbreaks in 2001 and 2007 demonstrate the disruptions to the food, farming, to visitors to the countryside, to rural communities and the wider economy that the disease can cause.

What role did geography play in influencing the spread and impact of the disease?

Once present in the fluid from blisters, saliva, milk and dung, the Foot and Mouth virus can contaminate objects, for example wellington boots, vehicle tyres and clothing, and spread for several miles. Favourable climatic conditions, for example the cold and dark, enable the disease to survive for long periods of time.

During the 2001 outbreak, it is thought that several conditions contributed to the origin and spread of the disease, including:

-

The inclusion of infected meat in swill (i.e., catering waste, possibly including the use of meat imported illegally)

-

The feeding of untreated swill to pigs

-

A delay in diagnosis of infected pigs

-

The infection of sheep by a virus plume

-

The undetected disease in sheep for weeks

-

Large numbers of sheep movements

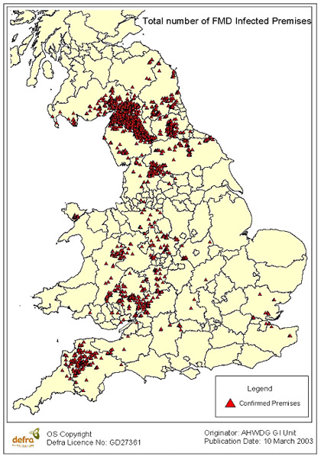

The first case of FMD was detected at Cheale Meats abattoir in Little Warley, Essex on pigs from Buckinghamshire and the Isle of Wight. Over the next four days, several more cases were recorded in Essex. On 23 February 2001, a case was confirmed in Heddon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland, from where the pig in the first case had come from; this farm was later confirmed as the source of the outbreak. In the weeks and months that followed cases were confirmed across the country. The map below shows the location of premises infected by FMD. Cumbria was the worst affected area of the country, with 843 recorded cases.

Location of premises infected by FMD

The rapid geographical spread of the disease highlighted two changes in farming practices.

Firstly, the delay in detecting the outbreak in Northumberland and the considerable movement of animals that occurred in the three week intervening period, two million sheep were moved around the country during this time with some animals being bought and resold though markets in different regions of the UK over very short time periods.

Secondly, it highlighted the centralisation of animal slaughtering and processing which involved animals travelling long distances to a small number of large abattoirs determined by major supermarkets rather than being taken to a local abattoir.

Interestingly, the 2007 outbreak was caused by a completely different combination of factors. Then, the virus escaped from the government funded Institute of Animal Health (IAH) and pharmaceutical company Merial laboratories in Pirbright. The virus entered the drainage system which combined with heavy rain, building work and vehicles moving to and from the site led it to spread and infect animals on nearby farms.

What were the immediate effects of the disease on different sectors of the rural economy?

When the first case of FMD was detected in 2001 the Government introduced a range of measures to control and eradicate the disease. These measures included:

-

A ban on meat and live animal exports;

-

Restrictions on the movement of animals (including a total ban on livestock movement for 10 days)

-

Granting additional powers to local authorities to close public rights of way

Farmers with animals thought to be infected had their livestock compulsory slaughtered. Farms in infected areas (but where animals did not get infected with the virus) were subject to tight restrictions preventing their movement off the farm. There was also a large drop in demand for farming support services, particularly haulage. All livestock markets were also closed.

As a result of the additional powers granted to local authorities to close footpaths, and indeed the closure of almost all footpaths at the start of the outbreak; many visitors and tourists thought that Britain’s countryside was closed for business. The drop in visitor numbers reduced trade for a wide range of rural businesses, including hotels, pubs and shops.

Losses extended to other industries besides farming and tourism, many located outside rural areas. These included suppliers to those industries, such as livestock hauliers and makers of farm machinery; activities dependent on countryside access, such as fishing, shooting and the horse business; suppliers to countryside users, such as makers of outdoor clothing, hirers of marquees, cycle manufacturers and guidebook publishers; and activities dependent on overseas visitors such as theatres and language schools. Some little-known businesses suffered heavy losses - for example, the maggot-rearing industry!

Collectively, the FMD outbreak of 2001 cost the UK £8 billion.

Although much of the countryside remained open for business during the 2007 outbreak, the Country Land and Business Association (CLA) estimated the financial costs of the outbreak to be in excess of £302 million on the agriculture and tourism industries alone.

Importantly, these immediate effects demonstrate how farming is interdependent and intertwined with the wider rural (and urban) economy.

Are we still feeling the impacts of the outbreaks today?

The 2001 and 2007 outbreaks were not merely costly and damaging economically and socially; they also marked a turning point in public attitudes to food production and have led to changes in Government policy. Combined with Independent Reviews of the Government’s response to the outbreaks carried out by Sir Iain Anderson and The Royal Society (which made a series of recommendations in the event of any future outbreaks) the 2001 and 2007 outbreaks continues to shape the way in which livestock keepers farm each and every day.

Firstly, the outbreaks have led to improved contingency planning and preparedness. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), for example, has a ‘Framework Response Plan’ setting out the roles, responsibilities and procedures that should be put in place to manage an ‘exotic disease outbreak’ the moment there is a suspected case of disease. The FRP is regularly revised and subject to public consultation prior to being laid before Parliament each year. Most recently, the FRP was used to prepare for an outbreak of Avian Influenza.

Secondly, the outbreaks led to the implementation of a series of biosecurity measures – these are a set of practices which, when followed collectively, reduce the potential for the introduction or spread of animal disease onto and between farms. During FMD and in the event of further outbreaks, Defra advises that farmers keep species of livestock separate where possible; be aware that sheep do not always show obvious signs of disease but could inadvertently infect other animals; to keep everything clean, for example boots, clothing, equipment, vehicles and to ensure that disinfectant and cleaning materials are used at farm entrances and exits.

Thirdly, traceability and providing a clearer picture of when and where livestock are moved and physically located, through the use of bar codes, animal passports and ear tags has come into force. In September 1998, the Government launched a computerised Cattle Tracing System (CTS) to record the movements of cattle from birth to death. CTS logs the movements of all cattle born or imported into Britain and issues them with individual cattle passports. Electronic Identification (EID) for sheep came into force in 2009 and means that sheep born on or after 31 December 2009 must now be electronically identified (unless they are going to be slaughtered within 12 months of age). Pigs also need to be registered with Defra and a movement licence completed before they are moved off a holding. These systems make it possible for Defra to trace animals exposed to a disease risk and give assurances to buyers and the public about an animal’s life history.

Fourthly, the outbreaks have led to new ways of thinking about how disease outbreaks are funded. Defra currently spends £330 million each year on animal health and has to meet the additional costs of any disease outbreaks in England, Scotland and Wales. The Coalition Government is currently developing proposals to share the costs for dealing with disease with animal keepers. The Government has established a ‘Responsibility and Cost Sharing Advisory Group’ to develop these proposals by December 2010 (they could include requiring animal keepers to take out insurance for example). In June 2010, Defra announced that the Animal Health and the Veterinary Laboratories Agency will merge to form a single agency to combat animal diseases.

How has the recession impacted upon the rural economy?

A range of global economic factors such as increasing fuel costs, food prices and currency fluctuations had already caused instabilities and problems for those living and working in rural places before official statistics showed the UK had entered a recession.

There was a time lag before the recession itself was felt in rural economies. And the impact of the recession itself in rural areas has been diverse. On the one hand, some rural places benefitted from their proximity to urban areas with strong economies and some remote rural areas were insulated and saw vibrant local economies. On the other hand, some rural places have suffered from being close to areas which have seen major slowdowns in key sectors. For example, upheavals in the car industry have impacted directly upon many rural manufacturing businesses in the West Midlands, Peak District and Oxfordshire.

Just as the impact of the recession was varied, so too were the policy measures developed by Government to help. Many rural businesses had difficulties securing funds from the bank and maintaining cash flow; relying instead on personal lines of credit (i.e., using a credit card). Around 200,000 people living in rural England do not have access to a bank account of any kind. There were also too few debt advisors working in rural areas with businesses and communities. Citizen Advice Bureaux (CABx) saw demand for its services increase by 53% in rural areas during the last 6 months of 2008, especially in villages. The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) funded 500 face-to-face debt advisors yet only 24 of these advisors operated in rural areas; leading to three to four week wait for an appointment.

Since May 2009, Defra has been producing monthly ‘dashboards’ which present a range of statistics to give an indication of the effects of the recession in rural areas and their path to recovery. The dashboard is updated on a monthly basis. The five indicators used are: claimant count, economic activity, redundancies, house prices, and business insolvencies. The dashboard shows that on average, rural areas are performing on a par with urban areas. For example, the August 2010 dashboard found 1.8% of the working age population in rural England was claiming unemployment related benefits, compared to three and a half per cent of the country as a whole. The dashboard also reveals how rural areas were slower into the recession and therefore emerging from it more slowly.

Is there such a thing as a single rural economy and which parts of it are growing and in decline?

In 2008, Matthew Taylor (former MP for Truro and St Austell) published ‘Living Working Countryside’, a Government review of how land use and planning could better support rural businesses and deliver affordable housing. Here, Matthew Taylor challenged the romanticised view of the countryside as being one that is driven by agriculture. Although agriculture still has a vital role to play in rural areas Taylor used the term ‘rural economies’ to describe how they are more modern, diverse and dynamic than this, and often characterised by a higher proportion of small and micro-businesses, self employment and home working.

Although there may be no such thing as a single rural economy, many of the sectors in rural economies are changing. The Coalition, in its Programme for Government, aims to boost enterprise, support green growth and build a new, more responsible economic model, one not dependent upon a narrow range of sectors. This presents some real opportunities and challenges for rural economies.

The food and drink industry has traditionally been a key employer in rural areas, contributing £80.5 billion to the UK economy and employing more than 3.6 million people. Although the majority of growth opportunities are expected to come from innovative products (for example health foods), signature specialities including branding foods is becoming increasingly important. For example, Leicestershire is home to Stilton and Red Leicester cheese and the Melton Mowbray pork pie; food and drink here accounts of 16% of manufacturing jobs.

The UK’s ageing population is expected to create an increase in demand for health and social care services – this demand is forecast to grow at a faster rate in rural areas compared to urban areas. The population aged 65 years and over is expected to increase by 62% between 2009 and 2029 in rural areas (compared to 46% in urban areas). According to an organisation called NESTA, healthcare services for the elderly will grow annual by four per cent between 2008 and 2013, generating an additional 111,000 jobs.

The Coalition Government has proposed a series of measures to realise a low carbon economy - including establishing a green investment bank, promoting anaerobic digestion, establishing a smart grid and encouraging marine energy. Rural areas, with their high rates of entrepreneurship, natural resources and heavy reliance on heating oil, LPG or solid fuel for heating, have huge and unique potential to benefit from this low carbon transition (particularly in the generation and use of renewable energy).

Rural areas tend to rely upon tourism related activities just as much as or more so than urban areas. In 2009, the tourism sector was estimated to have contributed £52 billion to the British economy and employed 1.36 million people. By 2020 it is predicted that the sector will generate an additional 250,000 jobs.

However, one of the drivers of several rural economies – the public sector- is likely to diminish over the next few years. Economic analysis undertaken by Rose Regeneration and the Rural Services Network (RSN) has found that one in three jobs in rural local authority areas are in the public sector. Prime Minister David Cameron's home county of Oxfordshire has the highest number of public sector employees (96,000 jobs), with Norfolk, Devon, Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, Suffolk, Somerset, North Yorkshire, Cornwall and County Durham also having high public sector job counts.

Links:

Jessica was interviewed in November 2010.

Jessica Sellick’s Biography

Jessica has a background in land management and environmental issues. She has worked at Defra (on a project looking at establishing new funding structures for tackling farm animal diseases post FMD 2001) and the agriculture and food programme at the new economics foundation (an independent think-and-do tank based in London). Jessica now works as a co-director at Rose Regeneration, an economic development practice based in Lincoln. She has a PhD in Geographical Sciences from the University of Bristol and is a Chartered Geographer (CGeog) at the RGS-IBG.