May 2015

Since 1990 there has been a very significant reduction in the numbers of people living in absolute poverty, with a halving of the number of people who live on less than $1.25 a day. However global inequality is a growing problem with the divide between the world’s economic elite and the world’s poorest people getting ever larger. By examining the nature of inequality generally and more specifically by examining a case study of education in India and the way in which Oxfam are working to bring a greater degree of equality to this sector, as well as what is causing the general continuation of inequality, we can broaden our understanding of this issue and explore some of the different ways inequality can be managed now and in the future.

What is inequality?

Everyone experiences inequality at some point in their lives. Before we have even been born many aspects of our lives have already been decided by the era and place into which we first have contact. What we will and will not experience is, for the most part, not decided just by the genes we inherit from our parents and how they parent us, but rather by the economic, social and environmental context of the place we call home.

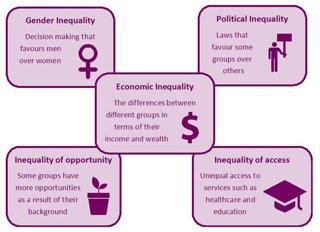

Inequality in geography refers to the idea that different people experience different standards of living. This can be economically, with differing levels of wealth and income and politically through differing rights and freedoms, as well as through a variety of other spheres, such as access to health care or education (Figure 1). While it is impossible to have a completely equal global society, the scale of inequality in the world is growing both within and between countries and in terms of and economic measures of poverty as well as other forms of inequality. Recent evidence indicates that everyone is likely to benefit from societies being more equal (Wilkinson and Picket, 2010), not just the world’s poorest people. For example, a more unequal society is a less healthy one for everyone within it, regardless of their socio-economic background.

It is the spatial distribution of inequality that is of particular interest to geographers; as well as actions to try to reduce the absolute number of people living in extreme poverty and address the inequality gap. These concerns are also shared by those who are working to reduce levels of poverty and inequality such as international organisations, governments, non-government organisations (NGOs) and community based organisations.

Figure 1 Some different forms of inequality

How is inequality experienced globally?

At the heart of inequality is the idea that whilst economic growth is increasing living standards generally, including the incomes of the world’s poorest people, it is providing greater benefit to those relatively few people who are already wealthy rather than the majority who are not. The current picture of inequality reflects this: the world’s richest one percent of people share a combined wealth that is equivalent to that of the world’s poorest 3.5 billion people (Fuentes-Nieva and Galasso, 2014). This situation has been criticised on a number of levels, not least a moral one. For example, the international NGO Oxfam argues that such inequality is unsustainable, hinders poverty reduction efforts and makes resilience to future economic and environmental change much more difficult (something that is explored further in the case study in the second half of this piece). Across the globe, wealth and power have become synonymous and those with both may be seen to make decisions that may serve to continue or enhance their own position.

What are the causes of inequality?

The prevailing global economic model is capitalist in its nature, being based on private ownership of industry, open markets and free trade for the purpose of generating wealth and creating a profit. This system is one which can promote and do well from competition in the markets for goods and services as prices for these are driven by supply and demand. This is known more broadly as a free-market economy. A free market does not run independently of human actions and the many of the decisions made by politicians about how the free market operates have influenced the growing gap between the world’s richest and poorest.

Since the end of the Cold War in 1990, more and more countries have become part of a free market system, both within their national economies and within the global market. This has come about as a result of political decisions that allow more open trade, alongside other drivers of globalisation such as increased global demand for goods, the use of key raw materials that only some countries can provide, greater access to world markets due to improvements in (and the subsequent reduced cost of) transportation technologies and international trade agreements which have sought to remove resistance to open trade (such as import tariffs or trade restriction). The outcome of this has been that the direction by which finances travel has changed both internationally and within countries, though it is equally important to note that there are many different forms of capitalism, and free markets differ in their nature from country to country, and indeed from region to region. Profit from free trade has increasingly found itself in the hands of global industries, which in some cases have become more ‘wealthy’ and influential than some national governments. As more countries have begun trading internationally, so industries have sought to maintain the profitability of their industries by expanding the markets for their produce and seeking competitively priced raw materials and labour costs (often lower) for their production processes.

When constitutional and political barriers have presented themselves to this form of management, some industries have used their economic influence to sway those in power, such as national governments or international organisations to support their corporate agendas. Such actions might span open and legitimate lobbying of decision makers, whilst at other times this may include illegal actions such as corruption.

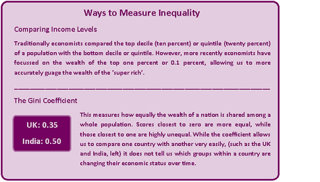

Figure 2 Two of the ways we can measure economic inequality

It is important to remember that there are other, less controllable, causes of inequality too. A combination of social, political and environmental factors (such as extreme climates and few natural resources) may contribute to poverty and inequality in a country. Sustainable economic decisions can overcome barriers such as these and there are many examples of regions and countries that have challenged these geographical factors, such as South Korea in the 1960s which saw average yearly growth of over eight percent in that decade (Nationmaster, 2014).

What can we do to manage inequality?

Many governments have historically made efforts to reduce their own internal inequality as well as support efforts to reduce inequality globally, for example by helping to provide an environment in which businesses of all sizes can prosper, more jobs are created and peoples’ incomes rise.

One way that inequality can be examined is through the taxation system a country operates. Money raised through taxation can be used to redistribute wealth within a country if the richest in society are taxed a higher percentage than the poorer (known as progressive taxation). The same can be said of industry and corporate taxation can be levelled in the same manner. In terms of progressive taxation it argued that it is better that tax is charged on people’s earnings rather than their spending. In the latter, poor and rich alike will spend the same on the additional tax on an item they both buy. However for the poorer people this tax will often represent a greater percentage of their earnings and so in effect, they will be paying proportionately more in tax as their disposable income is that much lower.

Another way to address inequality is to ensure that a greater percentage of state funding is directed towards key services such as education and healthcare. Public services, because they are free or provided with relatively low cost to the user, may be used more by poorer people than those with higher disposable incomes, who are more likely to pay for private education and healthcare. However, we should also recognise that in many developing countries the services provided by the state may not be universal and may be of a low standard and many poor people will often pay for access to privately run health and educational service.

This inequality of access to services is compounded even more in the poorest nations than in more developed ones and the effects in these are also felt more acutely. For example, reduced public funding of hospitals and clinics in poorer nations may mean that essential midwifery services become stretched which could result in a rise in otherwise avoidable infant mortality: which may be felt by the poorest families.

The spending of tax revenue does not have to be confined to health care and education, though these public services can be key drivers for social change. For example, investment in transport infrastructure, from a road linking a village to its nearest town to mobile coverage or air freight facilities, can help people gain access to new markets. In addition, government welfare programmes can also provide a ‘safety net’ for those times when other factors (such as a drought) make their monthly expenditure less predictable.

Case Study: Tackling educational inequality in Delhi, India

Educational inequality in India

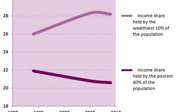

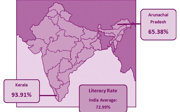

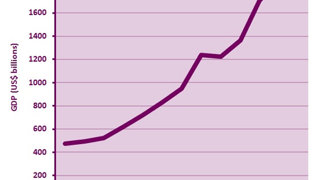

India has experienced rapid economic growth since the early 1990s (Figure 3). While some Indians have seen their personal wealth grow in real terms during that period (the number of billionaires has risen from two in 1992 to forty six in 2012), most Indians have seen a widening gap between rich and poor and the creation of what has commonly been termed a ‘two speed India’ (Figure 4 and 5).

Figure 3 The rise of Indian GDP over recent years. Source: World Bank, 2012

Figure 4 The widening gap between rich and poor in India Source: World Bank (2013)

Figure 5 There is a huge development divide between the different states in India. If we consider particular groups of Indians we see further alarming gaps. For example the female literacy rate in Bihar is 38.5%, lower than the national average of 43.7% in 1981. Source: Ministry of Home Affairs (2011) and Central Statistics Office (2012)

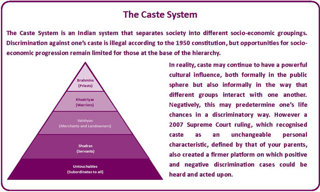

Although outlawed by the 1950 Indian Constitution, the shadow of the caste system (Figure 6) remains in the structure of society and continues to influence the opportunities presented to its citizens. Those from an upper caste still tend to dominate politics and almost all of India’s billionaires come from this group. Other social inequalities such as religious prejudices and limited opportunities for females outside the home also have roles to play as well as tribal links which many parts of India still support

Figure 6 The Caste System in India

Access to education lies at the heart of a person’s ability to have opportunities that will improve their livelihood (known as improved social mobility). The more educated someone is, the more chance they have of obtaining a well-paid job and having their voice heard politically. At the moment, the wealthiest Indian families usually pay for their children to receive private education because there is some inequality in the way in which education funds are distributed making the quality of resources available to teachers (such as books and school buildings) in some areas very limited. This can exacerbate the situation of limited opportunities for the poorest people and a widening of the societal and economic gap between them and the Indian elite.

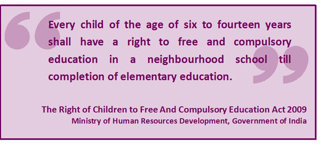

Figure 7 The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act. The Act also presses that higher quality schools should be a priority for India’s children, not just their enrolment in an institution.

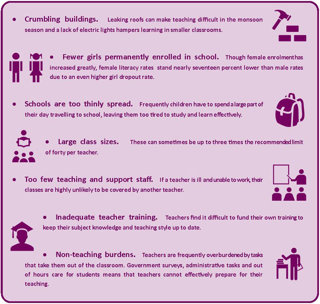

Despite the 2009 Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (Figure 7), India’s poorest children do not receive the same quality and quantity of education as their richer peers. This is evident in a number of ways, most of which are similar to the problems seen in other developing countries (Figure 8). However there is also evidence that teachers themselves can act in discriminatory ways towards their students in some schools, providing or denying learning opportunities to some students or turning a blind eye to cheating in state exams. Other causes of this inequality are not so clear. A lack of central funding for India’s schools lies at the heart of the problem (3.7% of India’s GDP is spent on education compared with 8% in the UK) but this is rarely spent evenly across the country or a state as different schools attract different levels of funding and there is more localised control of education budgets. Despite Indian legislation stating that twenty five percent of private schools should be reserved for poorer children who receive government funding, these can still be low cost schools that are subsequently underfunded and the law is adhered to in a somewhat inconsistent manner. A lack of electricity, or an inconsistent supply, especially in rural India, can mean that classrooms can be dark and with overcrowding, many students find it difficult or impossible to learn. A lack of suitable toilets and hand washing facilities is also a problem, especially for teenage girls who are deterred by the lack of privacy these toilets provide as well as an inability to remain clean during menstruation.

Figure 8 Some of the reasons why poorer students receive a lower standard of education to their wealthier peers

Poor sanitation means infections and diseases spread more easily in poorer schools and hence absenteeism through sickness is more likely. Though these conditions deter children, parents may also be reluctant to send their children to school and fewer young graduates aspire to be teachers in state run schools.

Figure 9 The crumbling school kitchen at Kumbaradi School, Karnataka, India. With poor facilities most schools can only provide students with a simple porridge for their daily lunchtime meal. (Source: Author’s own)

A private education does not necessarily guarantee a better standard of teaching and learning. The low budget private schools in the Indian education system, which are still beyond the budgets of many families, operate with large financial deficits and often with under qualified teachers whom, as a result of state pressures teach through rote and intimidatory methods to students who may find learning difficult. In contrast, better facilities are often provided by the better funded private schools. As a result, many families go into debt in order to ensure that their children receive a decent education. In Uttar Pradesh, a state in Northern India, some parents will to spend half their combined annual income on school fees, creating an economically unsustainable lifestyle for the family and enormous pressure on their children to obtain well paid employment (Seery, 2014).

Figure 10 A student in Karnataka, India. Many children travel long distances on foot to reach school every day leaving them tired and less able to learn. (Source: Author’s own)

Oxfam’s work on educational inequality in India

Oxfam has been working on a variety of inequality and development issues in India for over sixty years. An important strand of this relates to ensuring all young people have access to good quality free education, from primary through to secondary level.

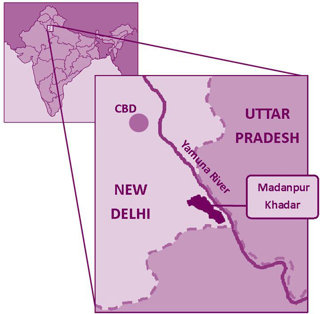

As part of this work, in 2012 Oxfam India worked with its longstanding Indian non-government organisation partner EFRAH (Empowerment for Rehabilitation, Academic and Health) to support children from the lowest income groups in Delhi to access good quality education. Their work has particularly focussed on improving the enrolment rates for girls in the Madanpur Khadar area of New Delhi (Figure 11). This slum district was historically a resettlement area for residents whom had previously been evicted from Delhi’s more central slums. The result of this was that Madanpur Khadar contains some of Delhi’s poorest and most marginalised communities.

Figure 11 Location of the Madanpur Khadar resettlement colony at the edge of New Delhi

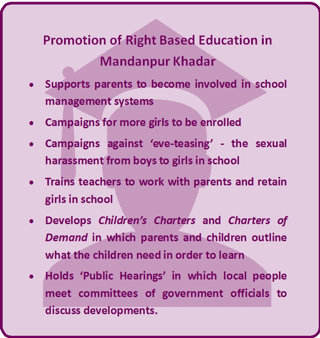

Education, even in a single district, involves a huge network of people and in recognition of this EFRAH is involving as many groups from this network – students, teachers, parents, local and national government – as possible in their mission to improve education in the area. It has supported and encouraged the formation of School Management Committees.

Figure 12 Oxfam India partner EFRAH and community from Madanpur Khadar, Delhi, India hold a Public Hearing. EFRAH supports the community to demand better education services and facilities from the government. (Source: John McIaverty / Oxfam GB)

Under the Right to Education Act, every government supported school should have a school management committee.

These are groups of concerned and involved parents and teachers who through meetings can create solutions to some of the day to day running problems of a particular school. These committees can also create long term aims and monitor the effectiveness of the schools, in a similar way to school governors in the UK. However in many schools, such committees have not been put in place and in other cases they are not being run properly. Therefore EFRAH is working with local communities and schools to make them work more effectively, such as by involving groups of parents that represent the socio-economic make-up of the local community more accurately.

This can help schools to become central vehicles in their communities for change and at the same time accountable to the communities they serve. Known as a ‘grassroots’ initiative, this type of development work makes local people the drivers behind the changes which itself goes some way to ensuring that stronger, more supported actions are taken. The programme has also been able to target changes that are specific to the needs of particular schools (Figure 13) rather than the ‘one size fits all’ policies inferred by the 2009 Right to Education Act.

Figure 13 Some of the work undertaken by EFRAH and Oxfam as part of the Promotion of Right Based Education Programme

Figure 13 Some of the work undertaken by EFRAH and Oxfam as part of the Promotion of Right Based Education Programme

The results have been positive. Around 2600 community members have been trained to more precisely understand the requirements and obligations written in the 2009 Rights to Education Act. A large number of girls’ awareness groups have been set up to provide more confidence for female students, especially those who have previously felt threatened by sexual harassment. Networks totalling around two hundred volunteers have been working to improve the physical fabric of school buildings in the district. Fifteen schools in the area have their staff enrolled in training courses that teach them how to best meet the needs of their own communities.

Figure 14 The end of the morning school shift in Mandanpur Khadar, Delhi, India. (Source: David Levene / Global Campaign for Education UK)

The annual presentations of a school’s Children’s Charter have met partial success. While they have provided a vehicle to allow public officials to listen to students the potential for wholesale action has been somewhat blocked by a lack of financial means to always make the required improvements. Giving people a voice and a ‘rights’ based approach is therefore only part of the challenge facing educational reform in India.

Conclusion

Global inequality is a significant challenge in relation to future economic, social and environmental sustainability. Despite very significant reductions in the numbers of people living in absolute poverty the gap between rich and poor people within and between countries continues to grow. This inequality can have a particularly negative impact on the opportunities of poor people. Real change is however possible and though the poverty gap widens in countries such as India, the statistics may mask the positive steps that can be taken to empower local people to drive their own actions. A ‘rights based approach’ coupled with larger, structural shifts, such as fairer taxation systems and a stronger and more accountable democratic system can allow those facing most inequality to find a way out of the unequal society into which they are born.

References

Central Statistics Office (2012) Directorate of Economics and Statistics

Fuentes-Nieva, R. and Galasso, N. (2014) Working for the Few, Oxfam International

Ministry of Home Affairs (2011) Census 2011, Government of India

Seery, E. (2014) Working for the many, Oxfam International

Times of India (2007) Can’t change caste, Supreme Court to college student, Times of India

Wilkinson, R. and Picket, K. (2010) The Spirit Level: Why equality is better for everyone, Penguin

World Bank (2012) World Data Bank

World Bank (2013) Poverty and Inequality Database

Unless otherwise stated, all information and data has been supplied by Oxfam International.

Key Words

Absolute poverty A state of living in poverty such that one's basic human needs are not being met.

Capitalism A world system that encourages private ownership of industry and its associated profits.

Free trade In reference to a free market economy, by which competition is set up between private industries and the price of goods and services is controlled by the levels of supply and demand.

Grassroots development initiative A project that involves the cooperation of local people to solve a locality specific issue.

Inequality A state in which some people obtain all the economic, environmental and social wealth while the majority have little.

Non-government organisation (NGO) An organisation or body that operates in a not-for-profit and apolitical fashion.

Relative poverty state of living in poverty compared others within a community, region or country.

Quality of life The general wellbeing of individuals and societies, indicated by measures such as health, education level and disposable income.

Social mobility The ability to create more social and economic opportunities for oneself by becoming more educated or by gaining wealth.

Trickle-down The idea of wealth (or changes in behaviour) making its way through society from those in most power to those at the bottom of society hierarchically.

Links