Introduction

Conducting oral history interviews is an excellent qualitative data collection method which helps to gain perspective of people’s interpretation of their own environment.

Oral histories can focus on various topics, explore personal experiences of events and, engage with specific places in which the interviewee has a meaningful connection. By sharing their lived experiences, individuals contribute valuable narratives that enrich our understanding of social, cultural, and historical contexts of places and events.

When conducted effectively - with careful preparation, ethical considerations, and active listening –oral history interviews serve as a powerful tool for capturing authentic experiences and preserving knowledge for future generations.

Use of oral histories in geography

Geographical research is a fundamental aspect of studying the subject. More often than not, when conducting fieldwork, the focus is primarily on quantitative data – measurable figures that can be analysed through graphs and statistical methods. However, qualitative data, which includes personal opinions and detailed responses, plays a vital role in understanding people’s connections to places and events.

When we study places or events, our interpretations are shaped by our own perspectives. In their nature, oral history interviews are often intergenerational (younger people speaking to older people, or vice-versa) and can help bridge gaps in perception and reduce misconceptions by exposing us to different cultural norms and lived experiences.

Oral interviews serve as an excellent starting point for independent fieldwork; offering valuable insights that can complement other forms of data collection in the field. They also provide a voice for individuals who may not have been traditionally represented in written records, ensuring that a broader range of narratives is included in geographical research.

Oral histories and the environmental movement

When we think of the environmental movement, high-profile activism tends to come to mind - such as Greenpeace campaigners protesting on oil rigs. However, this represents just one element of a much broader effort. Environmental advocacy extends beyond large-scale demonstrations to include policy reform, regulatory change, and grassroots initiatives that directly improve local communities. From scientists and policymakers shaping environmental legislation to individuals promoting sustainable behaviours in their daily lives, the movement thrives on a wide range of contributions.

Those engaged in environmental activism offer invaluable insights into both the physical and human elements of our world. By hearing from people who are (or were) addressing challenges from multiple angles - whether through scientific research, education, conservation efforts, or political activism - they help to contextualise their reasoning to create a sustainable future for generations to come.

Emma Must and Twyford Down

In 1992, Emma Must was a young librarian. On her commute to work, she could see the impact road building was having on her local landscape – Twyford Down in Hampshire. At the time, the government had plans to increase the number and capacity of the UK’s road network, including cutting through the chalk hill of Twyford Down. The planned road would destroy the Down’s chalkland ecosystem to alleviate traffic through Winchester and reduce the commuting time from Southampton to London by 7 minutes.

Emma was part of a group of activists who took direct action at the site of the proposed road in 1992 and 1993. She became one of the ‘Twyford Seven’, who were the first group of environmental activists to be imprisoned in the UK in sixty years. The M3 road was built and the Down destroyed. However, the pressure the anti-roads movement put on the British government led to media coverage and public debate about roads policy. In 1997, the New Labour government abandoned plans for dozens of road building projects. Emma’s oral history interview reflects on her experiences of the Twyford Down campaign and as an anti-roads activist, and on her more recent work as an environmental poet.

Interview clip: Emma Must describes her first experience of direct action on 13 December 1992.

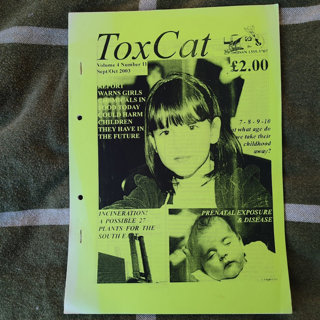

Ralph Ryder and toxins

Ralph Ryder was actively involved in environmental activism from the 1980s. He worked for Calor Gas at Ellesmere Port near Liverpool. His workplace was next door to a waste incineration plant that was burning toxic chemicals imported from mainland Europe. He was concerned about pollution from the plant and local people noticed that asthma seemed more common amongst the communities in the area. He established an organisation, Communities Against Toxics (CAT) and regularly produced a magazine, ToxCAT, to publicise research and campaign materials about the ill-effects of toxic waste emissions. He also gave talks to communities directly impacted - or at risk of being affected - by toxic emissions from incinerator plants all over Europe and the United States, often travelling at his own expense. He received several awards for his tireless campaigning efforts.

His role in CAT involved disseminating accessible, latest research-based information on the scientific and political aspects of toxic waste management, helping campaigners across Europe and the United States advocate for change.

Ryder’s efforts with CAT and other organisations put pressure on politicians to introduce regulation for the incineration of toxic substances, as well as the prevention of incinerator construction in various countries. His advocacy highlights the power of grassroots activism in shaping environmental policy and public awareness.

By using oral histories, researchers can delve into the origins of this work and how it has helped shape legislation and education around the incineration of toxic substances.

Further reading

Memoryscape – Audio Walks along the River Thames, Butler 2009

The Oral History Society - oral history guide for young people

File nameFiles

File type

Size

Download