‘Jamaica has an ecological crisis on its hands,’ explains Dr Liam Carr, who completed a PhD at Texas A&M University in January 2012. The reefs surrounding this tourist hotspot have been declining for the last 30 years as a result of overfishing, a loss of urchins, an emergence of algae and eutrophication. For other Caribbean nations, Liam’s message is clear: avoid Jamaica’s unsustainable path.

Living in the US Virgin Islands, Liam researched Caribbean marine systems and fish stock management. Given the many instances of overfishing in the Caribbean, he focused his attention on sustainable resource management programs.

He now works at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as a Senior Advisor to the Director of External Affairs, which involves exploring the intersection between science and decision-making.

How did Jamaica end up travelling so far down the wrong path?

For much of the 20th century, Jamaica’s fisheries were based on a healthy, largely unexplored coral reef system with healthy mangroves and seagrasses. However, from the 1980s onwards the Jamaican reefs began to steadily deteriorate.

This deterioration was sparked by the rapid and mysterious decline in the number of Diadema antillarum (a species of sea urchin that plays a key role in controlling levels of algae), beginning in 1983-84. The decline in urchins led to higher levels of algae, which acted to reduce oxygen levels in the water (euthropication). This can, in turn, negatively affect fish stocks. The marine habit is an interconnected system and so understanding what makes a healthy resource base goes far beyond questions about the use of that resource.

Much of the living coral is now gone. This degradation is going to take a lot of effort and a lot of time to restore. If Jamaica closed its fisheries down and nobody fished in the surrounding water (which is highly improbable), it may still take decades for the marine system - the coral, fish stocks and water quality levels - to return to its previous good health.

How can we understand the process of marine degradation?

We can liken the health of the coral reefs to a factory system. Imagine a smooth, clean factory with lots of materials coming in all the time, on time, and with well-trained workers running it efficiently. This is to say that a healthy coral reef system produces a high quality output of fish and sea life.

Imagine that we now turn the factory off for a day, or miss a shipment – this would be fairly fine, since the factory is still there to work properly the next day. But if the system stalls day after day, or if pieces of the factory start to crumble, then its outputs will suffer accordingly.

The minute you degrade the infrastructure of that system, anything resulting from it will also be degraded. Losses in reef infrastructure are exacerbated by the mass removal of species that do particular jobs within the system. This is where overfishing comes in.

Are these problems limited to Jamaica?

What is happening in Jamaica is similar to the suffering experienced throughout the Caribbean – most notably, rapid and permanent loss of coral reef. It is ‘beyond critical’ everywhere in the Caribbean. There a very few places left that can say they have a really great, healthy system. But Jamaica is further down the wrong path than many others.

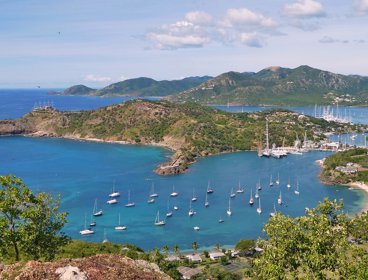

For example, Antigua and Barbuda (which I also studied) is much healthier than Jamaica – to use the analogy, their factory is working better than Jamaica’s. They are not perfect but their coral reef infrastructure is more robust. So any temporary losses as a result of overfishing, for even as long as a decade, has a greater capacity to recover quickly as long as the reef is intact and the resources are not totally lost.

How did you go about your research?

We did a meta-analysis, which involved comparing and contrasting a number of large primary and secondary datasets. To start with, we secured data provided by the Fisheries Division of the Antigua and Barbuda government. Because the data collection process in Antigua and Barbuda is still a very small operation, we then worked with the program officer who had personally collected most of the data. He talked us through it, which helped us to validate its reliability.

To get the same data for Jamaica we went to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations. Because of Jamaica’s relatively high international profile, the FAO had a large amount of data going back to 1950. However, there are a number of papers that warn against reading FAO data too closely, as some of it is self-reported and non-validated, so the accuracy is sometimes questionable. Further secondary and tertiary sources were used to confirm that the data was within an acceptable range – this took a bit of time.

Once you were satisfied with the fisheries data, what did you do next?

We pieced the two fisheries datasets together with other large economic datasets – to understand how the fish stocks interacted with the economy. There was the option to use a number of reliable indicators that dated back far enough, but we settled on using ‘percent GDP by sector’. The sector approach allows you to watch total GDP grow over time, whilst also comparing how the different sectors change in relation to one another.

Of course, you have to acknowledge that a ‘sector’ is very loosely defined. For example, ‘agriculture’ in Jamaica is very different to ‘agriculture’ in Antigua and Barbuda. The former includes a large amount of plantation agriculture, whilst the latter accounts mainly for fisheries – which is what we were interested in.

Why is unreported fishing such a large problem for the Caribbean?

If the formal fisheries in the Caribbean closed down, you could still see overfishing. There is that large an amount of informal and unregulated practices. People look to the oceans for their food. They catch fish for their families, and perhaps a little bit more to sell on the market. This unregulated trade, combined with a lack of fisheries data and the highly-localised scale of fishing effort, means that the Caribbean authorities cannot accurately model – and therefore manage – fish stocks without acknowledging that a large amount of uncertainty in their numbers persists.

By great contrast, our understanding of fishing in the the UK and Europe, such as in the North Sea is more certain. The costs and necessary investments to fish here are so high that economic incentives encourage the development of complex models based on large amounts of scientific data. Those models help define how much can be caught in a season, when to end the season, whether to close of an area and make it a spawning ground (even if it has no tourist value).

The struggle in somewhere like the North Sea is in making sure the models are accurate, since fishing is commercial and large-scale by nature. However, the Caribbean is less able to create such models. What they can do is cut down on the unknown, the unregulated. The percentage of unreported fishing is fairly large in the Caribbean and this impacts the ability to manage the fishery sustainably.

What are the benefits of reducing unreported fishing?

If you can squeeze the unreported amount of fishing down and get into the known areas, you solve a lot of problems. If you begin to understand any unreported areas then you can vastly improve your modeling and management.

If you know that there are people fishing in a certain area during the night without permission, then you can employ somebody to observe that area at night. If people are selling fish, as a hypothetical example, to Japan without reporting it, then it might make sense to have meaningful conversations with the Japanese government about development aid to regulate that market.

Is decision-making on a regional level important in improving one nation’s marine environment?

Antigua and Barbuda are two small islands in a chain of other small islands – Dominica, St Lucia, St Vincent, Trinidad etc. Any local effect that one of these islands does to protect a resource can provide benefits to neighboring islands and countries. Limited management success can be achieved alone.

For example, snapper spawned in say St. Lucia may ride ocean currents to Antigua before settling and growing into an ‘Antiguan’ adult snapper. With this connectivity between islands, overfishing in one country impacts the population of the same fish in another. So even if Antigua and Barbuda work diligently to stop over-fishing in their waters, if they depend on a declining, overfished population of snapper elsewhere to re-seed their stock, they will continue to see their stocks drop.

Because it is so large, Jamaica can experience positive benefits as a result of local action alone. However, Antigua and Barbuda has to be part of a larger regional team that relies on international agreements to negotiate effective regional fisheries management.

What does the future hold for the Caribbean and its marine environments?

In terms of developing a 21st century economy, the Caribbean must form a cohesive identity that respects the many different nations that have much in common both economically and culturally. Tourism will be the important economic industry, and each country needs to have a cohesive plan for building their own brand of tourism while still working with others to ensure that each draws benefits from the actions and economies of their neighbours.

Tourism is closely tied to the oceans. The pictures of a beautiful Jamaican beach – those images used to attract tourists – do not look as good when the water is not clean or when there is vast poverty nearby. The tourism industry has responded proactively to protect particular areas in Jamaica.

In some places, the economic losses in the fishery sector could be covered through tourism, which can be more lucrative. Fishermen can make more money by becoming a tour operator or sport fishing guide, for example. The Caribbean tourism industry recognises that the health of marine resources is closely tied to economic health.

Liam was interviewed in December 2012