November 2012

It is the invisible hazard: around 2 million people in UK urban areas at risk of sudden rain-related flooding. Recent research finds that this number of people is exposed to a 0.5 per cent risk of pluvial flooding, making such a scenario a 1-in-200 year event.

The research funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and presented at the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) conference 2012 also finds that by 2050 1.2 million more people are expected to be put at risk of pluvial flooding – 300,000 due to climate change (which is increasing the likelihood of flooding) and 900,000 due to urban population growth (with expansion into areas at greater risk of flooding). This article summaries the research and draws out links with the case study of pluvial flooding in Luton.

What is pluvial flooding and how is it being researched?

Definitions: Know your ‘F’s from your ‘P’s

Pluvial flooding occurs after short, intense rainfall which overflows the drainage system and surpasses the rate at which water can infiltrate into the ground. This can happen in areas not usually prone to flooding.

Fluvial flooding, by contrast, is caused by rivers bursting their banks. This is better understood and therefore more predictable than the lesser-known process of pluvial flooding.

In the news: Celebrity gardeners to blame!

Lord Krebs, the Government’s top adviser on climate change and flooding, has suggested that celebrity gardeners have made pluvial flooding worse. Garden makeover shows and celebrities such as Alan Titchmarsh have encouraged people to change their gardens in a way that increases surface run-off, The Telegraph reported.

Satellite imagery of England shows that the proportion of urban gardens with concrete paving has increase from 28 per cent in 2001 to 48 per cent in 2011. Such solid surfaces do not usually allow water to soak into the ground, as a grass lawn would. This may increase the amount of surface run-off, and therefore the risk of pluvial flooding.

Lord Krebs said: "How we adapt to these risks will be critically important to our future resilience: whether it's deciding not to pave over our gardens; or building in less exposed areas."

Methodology

The research project used three phases of analysis. Each phase used two scales of analysis: the national and the local. This was intended to understand the differences in decision-making at varying levels.

Phase 1: Computer modeling was used to understand the impact of climate change on pluvial flood hazards. This involved the analysis of maps of the wettest days under the current climate and under predicted future climates.

Phase 2: The risk of flooding is not simply a natural hazard. The impact of flooding is affected by the distribution of population and of vulnerable groups, in particular. This builds on the prior computing modeling phase, factoring in how population is distributed around the UK.

Phase 3: Interviews of up to 90 minutes were undertaken with key players and experts. National-level interviews included: central government departments, water companies and insurance companies. Local-level interviews included: drainage engineers, planners and emergency planners.

How can the socio-economic risks of a flooding be calculated?

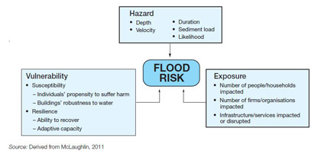

Diagram to show the influences on flood risk

Diagram to show the influences on flood risk

Flood risk may be increasing in certain places due to climate change. However, risk is never a result of physical processes alone – it also involves human factors. The risk of a flood can be calculated by considering the physical properties of the hazard, the vulnerability of individuals and properties, and the collective exposure of people and infrastructure to an event. The above diagram also takes into account resilience, or the capacity of people to cope with flooding.

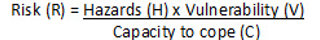

Risk equation for Edexcel students

But where flood risk assessments are usually based on the number of properties at risk, this report pays attention to the number of people at risk. This emphasises the impact on people and particularly the impact on vulnerable groups, such as the elderly.

But where flood risk assessments are usually based on the number of properties at risk, this report pays attention to the number of people at risk. This emphasises the impact on people and particularly the impact on vulnerable groups, such as the elderly.

The impact of flooding varies according to economic and social factors. For example, there are systematic processes that lead to vulnerable groups being over-exposed to the hazard. This is likely due to older, smaller terraced housing being more prevalent in low lying flat areas, close to a river. This is because these areas tended to be developed first during industrialization in the 19th and early 20th centuries. As towns and cities expand outwards, development is more likely to be on elevated land and now tends to be characterised by larger, more expensive housing.

Furthermore, many private renters are less affected by small-scale localized floods because they can find alternative accommodation relatively easily. However, the same private renters can be severely affected by large-scale flooding if they cannot find suitable accommodation in the same town.

What measures can be taken to mitigate against pluvial flooding?

Suggestions to mitigate risk

-

More accurate estimates of future rainfall

-

Widespread affordable insurance against flooding

-

Investment in drainage systems (including maintenance)

-

Buildings designed to be flood proof

-

Innovative management of surface water

Existing drainage systems can cause considerable problems in cases of flooding. Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) can be implemented to deal with run-off water, whilst also ensuring that any pollution or damage to the environment is minimized. A well-designed SUDS can help to:

-

Reduce run-off rates

-

Reduce the risk of flooding

-

Encourage natural ground water re-charge

-

Reduce pollutant concentrations in storm water

-

Reduce volume of surface water run-off

-

Provide habitat for wildlife

Source: Luton Borough Council (2012)

SUDS can be most effective when deployed in combination with surface water management plans and flood proofing of developments. This often involves separating storm water and foul water to increase drainage capacity and reduce the likelihood of sewage mixing with pluvial flood water. However, existing drainage systems will remain a part of the urban fabric for many decades to come. SUDS may not provide the most feasible option in all areas.

The report therefore makes different recommendations vary according to type of area, of which three are identified according to their relative levels of development (the density of buildings and infrastructure in an area).

Developed areas – Should ‘retro-fit’ (replace older equipment with new parts) drainage systems where possible. It is also important to identify and improve ‘pinch points’ (which struggle to deal with large flows of water) in the drainage system. The local landscape also requires attention to create safe routes for ground water to flow overland.

Undeveloped areas with pressure for development –SUDS (Sustainable Drainage Systems) should be implemented to effectively drain areas, whilst minimising pollution and managing water quality. Flood-proof building design is also important.

Undeveloped areas with less pressure for development – ‘Green’ (non-built-up vegetated areas) and ‘blue’ (urban spaces for storing water) spaces should be designed to effectively manage high rainfall. This should be supported through land use planning to set land aside for water management, especially to direct surface water away from properties.

Case study: Luton and the Ickley Close development

Luton, 30 miles north of London, is a large industrial urban centre which has rapidly expanded since 1945. The post-war infrastructure differs from the Victorian industrial urban forms of other towns and cities analysed in this study, which have older water management systems. With a recent history of pluvial flooding, Luton also has a surface water management plan.

The centre of the town is characterized by small Victorian terraced housing with little open space. This high density development means that it is more susceptible to flooding. However, further out more recent suburban developments are of lower density.

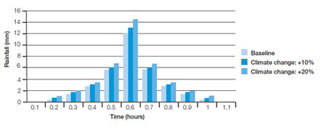

In line with the national urban average, 5% of the population of Luton is at risk from a 1 in 200-year pluvial flood. However, Luton would be more exposed to the hazard of pluvial flooding if climate change increases rainfall intensity. For example, a 20% increase in rainfall due to climate change would put 33% more people at risk. This is possibly due to the town’s flat topography, which would allow flood water to spread more widely than in other towns.

Graph to show changes in rainfall levels after applying different climate change scenarios.

Swales and soakaways in Ickley Close

In order to deal with excess run-off, Ickley Close, a new development in Luton, proposes to implement a SUDS through two main methods: swales and soakaways. This plan has involved a number of different player. It was put forward by a private consultancy company with the intention of satisfying the Planning Authority and Environment Agency.

Swales are designed to transport or store surface water run-off. They provide a broad shallow channel covered by vegetation, such as shrubs, and can also allow water to infiltrate into the ground. Through this process, particulates can be filtered out and the quality of the water can improve. In Ickley Close, swales are intended to deal with run-off from hard paved areas, which allow limited rates of infiltration.

Soakaways are essentially storage units. Dug deep into the ground (up to 17.5m below the surface in this case), they allow groundwater to recharge and have the effect of reducing peak flows. In Ickley Close, the soakaways would infiltrate run-off water into the underlying chalk. They are intended to accommodate the 1 in 100yr storm event even under an additional 30% of rainfall due to climate change in the future. However, care must be taken to limit the risk of pollution as the process of filtration is not a thorough as it is in swales.

Characterised by low-density housing, Ickley Close has is less susceptible to flooding than the Victorian centre of Luton. Furthermore, the efficient drainage systems of the nearby M1 motorway increases rates of infiltration in the immediate area. However, the continued development of vegetated land may pose future challenges for flood management plans in Luton.

Read more about the proposed development of Ickley close.

Conclusions and further reading

Local responses should be focused on adaptation. They should be developed through partnerships among different players (government, water companies, NGOs). Local authorities have a pivotal role to play in leading such a partnership, but often lack the powers, funding and skills to achieve their aims alone. Water companies, for example, therefore have a responsibility to modernise water drainage systems. Meanwhile, the Association of British Insurers should work with the UK government to make adequate provision for vulnerable groups.

Questions

Using the example of Ickley Close, Luton and one other case study, discuss the advantages and disadvantages of soft and hard engineering in flood management strategies. 15

Explain how flooding can impact on different socio-economic groups differently. 10