April 2017

Professor Marcus Power from the Department of Geography, Durham University researches geopolitics and energy transitions in South Africa – we spoke to him about his research on electrification in Mozambique and the changing geopolitical imaginations of ‘development’.

You can follow Professor Marcus Power on twitter @MarcusJPower

Key Questions

-

Access to energy services in sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest of any world region. How is demand increasing?

-

What are some of the global policies and goals that seek to improve this?

-

What is the energy infrastructure of South Africa and Mozambique?

-

‘Rising powers’ such as China, India, and Brazil have had a growing involvement in the provision of renewable energy technologies in South Africa and Mozambique. How are they helping?

-

Has there been some controversy surrounding this?

-

Who are the stakeholders in low carbon development in South Africa and Mozambique?

-

Who will benefit from these new energy transitions?

-

What are the geopolitics of new technology and energy development?

Access to energy services in sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest of any world region. How is demand increasing?

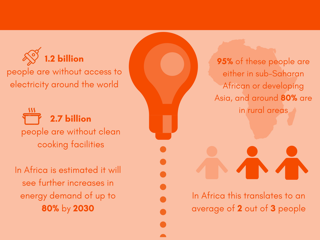

Access to modern energy services is paramount to reducing poverty, improving health and well-being, and in enabling ‘development’. Yet globally 1.2 billion people are without access to electricity and more than 2.7 billion people are without clean cooking facilities. More than 95% of these people are either in sub-Saharan African or developing Asia, and around 80% are in rural areas. In Africa, this translates to an average of two out of every three people, but this disguises huge variations across and within countries.

Africa’s economy and accompanying energy demand has almost doubled in size since the turn of the century and it is estimated it will see further increases in energy demand of up to 80% by 2030. Continued reliance on traditional fuels for cooking (especially biomass such as firewood, dung, crop residue and coal/charcoal) leads to millions of deaths from avoidable, smoke-related diseases, many of them children under the age of five.

What are some of the global policies and goals that seek to improve this?

International concern about the issue of electricity access has grown in recent years and a number of international global policies and targets have emerged that seek to address this. In 2011 the United Nations (UN) announced a commitment to providing “sustainable energy for all” (SE4All) by universalising access to modern energy services by 2030, improving energy efficiency and the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix.

These objectives have also since become part of one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agreed in September 2015 (goal seven). However, there is an implicit assumption that individuals or organisations and governments can intervene in order to transform poor people’s access to sustainable energy and that they will act in ways that are in the interests of poor people and poor countries rather than those of powerful elites. Some of these initiatives have been ‘top down’ (rather than working with communities and indigenous knowledge around energy from the ‘bottom up’) and important questions remain about the intended beneficiaries, about who gains and who loses.

It is also often unclear where the extra financing needed to meet these goals will come from. In addition to these global initiatives there are also projects being led by individual countries such as the Power Africa project established by the US under President Obama in 2013 or the UK’s Energy Africa access campaign launched in 2015.

It is also often unclear where the extra financing needed to meet these goals will come from. In addition to these global initiatives there are also projects being led by individual countries such as the Power Africa project established by the US under President Obama in 2013 or the UK’s Energy Africa access campaign launched in 2015.

What is the energy infrastructure of South Africa and Mozambique?

Carrying charcoal outside Savane, Sofala province, Mozambique © Joshua Kirshner

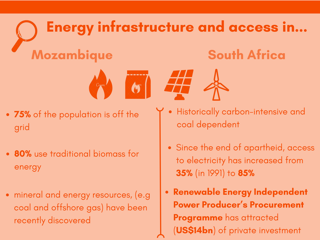

The energy systems of Mozambique and South Africa are very different which is partly why we choose them for our comparative analysis – to draw out some of the different kinds of challenges facing African countries and the different strategies being used by external partners to engage with them. South Africa’s energy system has historically been very carbon-intensive and coal dependent. Since the end of apartheid, access to electricity has increased considerably (to around 85%, up from 34% in 1991) but access remains uneven and a highly political issue.

In recent years, South Africa has also experienced an electricity generation crisis with frequent power outages, whilst tariff increases have made electricity unaffordable for many low-income households. The country has, however, become a leading destination for renewable energy investment (which has gone some way to enhancing sustainable energy access) following the emergence of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer’s Procurement Programme (RE IPPPP). This initiative has attracted R168-billion (US$14bn) of private investment into the supply-stressed electricity sector, allocating approximately 6.5GW of generation capacity, largely from wind, solar PV and concentrated solar power (CSP).

By contrast, characterised by a history of colonial underdevelopment and following decades of civil war, Mozambique’s energy system, has a strong dependence on hydro-power together with an extremely limited grid infrastructure centred on some of the largest urban areas and although electricity access is rising, around 75% of the population remains off-grid with approximately 80% reliant on traditional biomass for energy.

Recent discoveries of mineral and energy resources, particularly coal and offshore gas, has led to more optimism about the future prospects for national growth and development and represents a valuable opportunity for Mozambique to use the considerable revenues generated by the hydrocarbons boom to rapidly increase energy access. The government’s approach to electricity supply has however typically prioritised electricity for industry, for urban spaces and for export to regional markets.

The power house for a mini-hydro system at Majaua-Maia, a village in Milange district, Zambézia, Mozambique. The project was established by Mozambique’s National Energy Fund (Fundo de Energia, FUNAE) © Joshua Kirshner

The power house for a mini-hydro system at Majaua-Maia, a village in Milange district, Zambézia, Mozambique. The project was established by Mozambique’s National Energy Fund (Fundo de Energia, FUNAE) © Joshua Kirshner

Recently, ‘rising powers’ such as China, India, and Brazil have had a growing involvement in the provision of renewable energy technologies in South Africa and Mozambique. How are they helping?

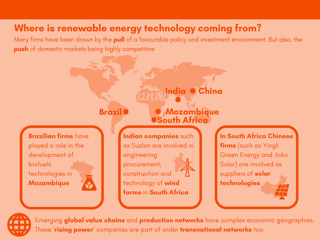

Although often referred to as a group, the ‘rising powers’ have very different patterns of investment and project development around renewable energy technologies (RETs) in Southern Africa. Although the presence of ‘rising power’ actors is highly variable there is evidence that firms from China and India, for example, are beginning to play a key role in the transfer and development of RETs in the region.

In South Africa, Chinese firms (such as Yingli Green Energy, Suntech, Jinko Solar, Chint and Powerway) are involved as suppliers of solar technologies. Indian company Suzlon and Chinese firms Guodian and Sinovel are also involved in engineering procurement and construction (EPC) and technology supply for wind energy projects whilst Brazilian firms have played a role in the development of biofuels technologies in Mozambique. India’s Tata Power and China’s Longyuan Power Group have also been involved in joint ventures with South African companies in developing wind energy projects.

In Mozambique, Indian credit lines have enabled the country to build its first solar PV module manufacturing plant which may help to reduce imports in the longer term. Many of these firms have been drawn by the ‘pull’ of a favourable policy and investment environment (such as RE-IPPPP in South Africa) or have been ‘pushed out’ by saturated domestic markets and intense competition domestically.

The ‘rising powers’ are also pursuing a myriad of different energy developments in each country (including some around high carbon energy resources such as coal and gas) which may serve to further entrench high carbon development pathways. It is also not the case that ‘rising power’ actors are now completely dominant or exclusively determining the path of low carbon development – established actors (such as European bilateral donors) remain significant whilst actors from other emerging economies (such as South Korea) are also playing an important role. In our research we found that attributing involvement or project ownership in RETs to any one ‘rising power’ can be problematic given that many ‘rising power’ companies are themselves bound up in wider transnational networks (of construction firms, renewable energy development companies, technology providers and national and international investment coalitions). Our work thus highlights the importance of tracking emerging global value chains and production networks around RET’s to better understand these complex economic geographies.

Has there been some controversy surrounding this?

The increasing presence of the ‘rising powers’ in Africa (especially China) has attracted considerable attention and some controversy in recent years with some debate about their roles as ‘new’ development donors and the impacts this is having on key challenges facing the continent around, for example, poverty reduction, democracy and sustainable development. Some observers have referred to a new ‘scramble for Africa’ as the ‘rising powers’ compete for strategic influence in the continent and the spectre of imperialism has loomed large over many of these debates with some commentators arguing that their interventions constitute a contemporary form of colonialism. Many of these narratives are however rather simplistic and often stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of the ‘rising powers’ themselves and the nature of their states and economies or from fears about what this may mean for the declining influence and significance of western donors and companies.

It is becoming clear however that the rise of Southern investors and donors like China, India and Brazil and the growing importance of South-South technology transfer is beginning to change the face of international development co-operation.

In Mozambique there has also been some concern about ‘rising power’ investments in high carbon resources like coal and gas (and in particular around how much the revenues generated will benefit ordinary people) whilst some of the large scale energy access solutions proposed by the Mozambican government and involving ‘rising power’ companies (e.g. large scale hydro-power projects) have been contested by community groups and civil society organisations who have highlighted the social and ecological destruction that they will cause or the lack of popular participation in their planning and design.

Who are the stakeholders in low carbon development in South Africa and Mozambique?

Low carbon development encompasses a complex mix of stakeholders from the public, private, national and international and political and economic spheres. Within each of the ‘rising powers’ there are a wide variety of central and local state agencies involved along with quasi-state agencies (such as export-import banks and credit agencies). There are also a wide variety of non-state actors including a panoply of private firms concerned with both high and low carbon energy sources and technologies.

Different firms and sections of the state within each of these ‘rising powers’ are engaging with different actors in each country in ways which defy simplistic narratives and explanations. In Mozambique and South Africa there are a range of different state agencies involved (concerned with development and different elements of the energy system). Industrial energy consumers also represent an important constituency here in shaping the nature of each country’s energy system as do national and international NGOs, established European development donors and transnational agencies like the World Bank. Regional development agencies like the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) also have a growing interest in energy access and low carbon transition along with pan-African organisations like the African Union who have sought to mobilise investment in renewables.

One of the most significant (and often most neglected) stakeholders are the communities concerned who have in many cases had limited opportunities to participate in energy planning and discussions around what and who energy is ultimately for. This is particularly true of Mozambique where electricity provision has historically been highly centralised and ‘top down’ with relatively few opportunities for community participation in planning, design and decision-making around energy.

Who will benefit from these new energy transitions?

This question of who will benefit from the emerging low carbon energy transitions unfolding in the region is absolutely key. There is no question that ‘rising power’ companies have found lucrative opportunities in emerging African markets like South Africa and stand to gain a great deal from these forms of technology transfer and infrastructure development. In terms of geopolitics, South-South trade flows and development cooperation of this kind have enabled the ‘rising powers’ to both widen their spheres of strategic influence on the continent but also to gain greater access to high carbon energy resources like coal and gas which are necessary to fuel their own domestic development. Consequently, there remain concerns that some of the principal beneficiaries to date have been states and business elites and that there have been relatively few benefits so far in terms of poverty reduction and sustainable development in Southern Africa. In our research we have argued that in order to fully understand this question of ‘who benefits’ it is necessary to better comprehend the specific political, economic and historical contexts of Mozambique and South Africa and the nature of the state (and the interests that they represent) in both countries. Key questions remain around the affordability of energy services given recent electricity tariff increases but also around the longer term sustainability of these energy technologies given the limited evidence of capacity building and skills development (e.g. in relation to the maintenance of RETs in Mozambique). There are also a variety of issues raised by the simultaneous pursuit of both low and high carbon development pathways and the tensions and contradictions that this generates.

Some solar panels In Mozambique end up for sale in second markets such as in the Xipamanine market in the capital city Maputo © Joshua Kirshner

What are the geopolitics of new technology and energy development?

One idea that has been popular in many recent debates about low carbon development technologies in Africa is that the continent is on the cusp of a clean energy revolution and that as the cost of RETs falls Africa can ‘leapfrog’ fossil fuels technology into a new era of green economic development. The precedent for this is seen to be Africa’s telecommunications sector, where the lack of fixed infrastructure led to the primacy of mobile phones for everything from democracy and health to banking. Mobiles, and the services available through them, reached areas landlines never made it to and so some see that kind of “leapfrogging” already happening in RETs vs. traditional energy sources.

Solar panels have been used to electrify schools and health centres in remote district capitals in rural areas such as at the Tengua health clinic, Milange district, Zambézia, Mozambique ©Joshua Kirshner

Fossil fuels are however likely to remain a key part of how African states seek to address energy access issues at least in the short to medium term and it is perhaps unreasonable to expect developing countries to do otherwise given the centrality of high carbon sources to the development pathways pursued by countries of the global North. There has long been a belief in development theory and practice that technology can offer a magic or ‘silver bullet’ solution to the problems faced by developing countries when time and again (e.g. with the green revolution) experience has proven otherwise. There are no simple solutions or quick fixes and it is naïve to think otherwise. Solutions need to be tailored to local contexts and knowledges and driven from the bottom up through community participation in planning and decision making. Decisions about which energy resources to prioritize, and where to build new infrastructure are not purely technical considerations but highly political. In terms of a more rounded view –the term ‘energy access’ is rarely problematized (this is about so much more than simply ‘plugging’ consumers into a grid infrastructure as many donors seem to believe) and we need to know much more about the role that energy plays in the everyday lives of people in the South. Energy is now widely regarded to be an ‘enabler’ of development, propelling activities in agriculture, trade, industry, health and education and attracting new investments and improving livelihoods but what is rarely discussed explicitly, however, is exactly who and how many will benefit.

Key words

Apartheid

This political system governed life in South Africa from 1948 to 1991. It enforced a racial hierarchy privileging white South Africans

Biomass

Fuel that is developed from organic materials, it is a renewable and sustainable source of energy used to generate power and electricity

Clean cooking

The use of preparation and equipment that makes cooking safe, secure and sustainable rather than potentially unsafe for people and environment due to lack of income and adequate materials.

High carbon development

Economic development based on carbon-intensive energy such as coal, oil and gas

Low carbon development

Economic development plans that use low emission strategies and/or promote economic growth through economy-wide decarbonisation, reducing dependence on fossil fuels in the development process

Off the grid

People and places not connected to the national electricity grid infrastructure

Rising powers or emerging economies

Rising powers are countries that are increasingly influential globally. This category includes the BRICS (the grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa)

Post colonialism

The analysis of the cultural, social and economic legacies of imperialism

Lesson plans

As a starter, ask students to consider how much energy and electricity they have already used today. Consider, has this energy consumption been provided through high, or low carbon pathways?

In order to introduce locations discussed in this case study; ask what students know about Mozambique and South Africa. Have they experienced, or do they have any particularly preconceptions of what energy supply may be like in these regions?

The class should divide into two; with each side researching and creating a fact-file on either South Africa or Mozambique. Consider, how is energy access changing in these locations?

The article introduces solar, wind, and biomass energy supply from India, Brazil and China. Ask students to choose one of the places. Student should research one of these and create an infographic on how this power supply works whilst also mapping (with annotations) the global reach of one of these manufacturers. How do wind farms begin life in China and travel to Mozambique?

The class as a whole should debate: ‘who will benefit from low carbon development?’ Encourage consideration and comparison of local, national, and global scale and communities.

Links

Sustainable Development Goal 7

Clean Development and Low Carbon Transitions in Southern Africa, Project Blog

Professor Marcus Power, personal page

Mozambique needs a community-driven approach to electrification, The Conversation (2015)

Marcus was interviewed in April 2017