October 2015

Dams generate a considerable amount of energy for Brazil and hydroelectric power has played an important role in creating a fast growing economy for the nation. With eighty percent of the country’s energy coming from hydroelectric sources (compared to seventeen percent globally) the proliferation of the industry has been celebrated by some campaigners as well as demonised by others, with observers in the latter group increasingly raising concerns about the impact the dams have on the hydrology regimes of the country. A new large scale hydroelectric dam, the Belo Monte, is due to be completed in 2016 on the Xingu River in the state of Pará. While the new dam has been marketed as the guardian of Brazil’s energy security, the social and environmental impacts of the structure have also been called into question.

Hydroelectricity in Brazil

Brazil has a long history of utilising the power of its many large rivers and is second only to China in the proportion of the country’s energy that is generated using hydroelectricity. The country’s first hydroelectricity plant was completed in 1883 on the River Ribeirão do Inferno and there are now over forty hydroelectric dams operating in Brazil, with capacities ranging from 237 to 14,000 MW (Global Energy Observatory, 2015). Events of history and Brazil’s natural capacity for hydroelectric power generation are behind much of this growth and dependency. The drop in subsidised coal and oil imports during World War One left Brazil facing an energy crisis and the need for a stronger domestic supply of energy spurned the Brazilian government to look towards bigger investments in new forms of electricity generation. With over 25,000km of river channel in the country’s eight largest river systems alone, and drainage basins that are consistently fed by high levels of precipitation, hydroelectric power seemed an obvious choice, and a widespread dam building programme began; focusing primarily on large scale plants on the biggest rivers.

Where and what is the Belo Monte Dam?

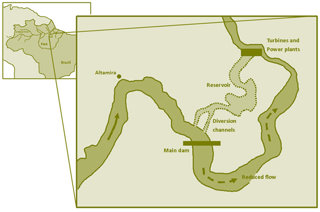

Work on the Belo Monte Dam complex began in 2013 with an estimated three year build time. The complex is actually a series of three connected dams, with two twelve kilometre diversion channels taking the water through to one of two power plants. Though dam construction in Brazil is not unusual, this complex has drawn considerable attention due to its sheer size: when completed the dam will be the world’s third largest in hydroelectric capacity behind by China’s Three Gorges Dam and the Itaipu Dam on the border between Brazil and Paraguay.

Location of the Belo Monte Dam complex

Sitting on the Xingu River (a southern tributary of the Amazon River) and consisting of three joined dams, the Belo Monte will have a capacity of over 11,200 MW, believed to be enough to supply the whole of Pará state. It will cause the flooding of an area roughly 2km3 in a series of lakes but consisting mostly of the Dos Canais Reservoir.

What benefits will the Belo Monte Dam Complex bring?

The abundance of dams in Brazil has allowed the electricity they generate to become markedly affordable to Brazil’s 202 million strong population, nine percent of whom live below the poverty line (World Bank, 2015). Brazilian president, Dilma Rousseff and her predecessors have recognised the importance of the country securing a domestic energy supply as Brazil undertakes rapid economic development and the Belo Monte Dam complex forms part of this agenda for safeguarding investment in new industries from transnational companies. By 2021, Brazil is expected to be the world’s fifth largest economy (Forero, 2013) and Brazil’s National Energy Planning Agency agrees that preparing for this eventuality by dam building now is Brazil’s best chance of fulfilling its economic potential in the future.

While Brazilian dams may not make perfectly sustainable solutions to energy insecurity, their modelling and construction has evolved considerably since 1883. Despite its size, the Belo Monte dam has been designed and positioned in such a way that, considering its relative scale, it will flood an area of land five times smaller than the Tucurui dam that was constructed twenty nine years previously (Forero, 2013). A smaller flooded area will mean that less habitat will be submerged and fewer local residents will be need to relocated from their lands. Other new initiatives have also found their way into the dam’s design to make it more sustainable: fish ladders (sequences of stepped pools that allow fish to navigate safely into higher waters) have been installed and smaller diversion channels and corridors for wildlife are also planned.

There is conflict over whether the environmental integrity of the Xingu River will be under threat by the Belo Monte Dam complex. (Flickr Source: Lia Bravo)

As an alternative to fossil fuel combustion, the Belo Monte Dam complex represents part of a clean and renewable solution to Brazil’s future energy needs and during its operation produces no greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide, functioning as a carbon neutral facility whereby running energy needs are met by the dam’s turbines in real time.

If the Belo Monte dam follows in the footsteps of some of its predecessors, it also holds the potential to modernise the living conditions of some of the Pará region’s residents. The consortium behind the dam’s construction has a social responsibility to relocate the at least twenty thousand people due to be displaced by the reservoir the dam will create (Amazon Watch, 2015). Relocation packages often involve the building of new villages that have more modern infrastructural works (such as running water and sanitation standards as well as electricity generated from the dam itself) than the villages that are submerged and so there is the potential that the Belo Monte dam complex will, in one respect, improve the lives of those within its locality on the Xingu River (Forero, 2013).

What impact might the Belo Monte Dam create and why is the new dam surrounded in controversy?

The new dam complex represents a substantial investment in future hydroelectricity. The US$17 billion cost of the dams come in part from the Brazilian government and also from the dam’s operating company, Electronorte. Anti-government protests in Brazil in 2013, 2014 and 2015 took place in response to the amount of money being spent to host on the 2014 football World Cup and 2016 summer Olympic Games. These protests have also highlighted more generally the injustice many poor Brazilians feel when they see their government spending money on large infrastructure projects rather than poverty alleviation and plans such as the Belo Monte Dam complex have prompted similar feelings.

The Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) who granted the license for the Belo Monte Dam complex in 2010 have faced numerous anti-construction campaigns from high profile celebrities and the plans for the complex have gone through several redrafts since it was first conceived in 1975. In order for the dam to guarantee a constant supply of energy, technical staff and hydrology engineers have long recommended that almost the entire flow of the Xingu River would have to be diverted through a series of other dams after the Belo Monte was completed. This is because the Xingu River experiences more marked changes in its flow between the wet and dry seasons and so other dams would need to be in place to control the amount of water in the river at any given point in time. As a tributary of the Amazon River, the management of the Xingu River could therefore have a lasting impact on the regime of the larger river and engineers and environmentalists fear that it would start the management of Brazil’s drainage basins down a highly mechanised course from which it would not be able to reverse. Before 2021, Brazil has plans for thirty four large scale dams around the Amazon basin which many fear will turn the river into a series of interconnected, concrete-lined reservoirs (Forero, 2013).

The social impacts of the dam are also cause for concern. The estimates of the number of people who will be displaced by the Bel Monte Dam and the Dos Canais Reservoir only account for those living in an established urban settlement such as nearby Altamira. In addition to these are the thousands of indigenous people living alongside the Xingu River who are living a traditional way of life, particularly those downstream of the Belo Monte Dam complex. Here there will be flow reductions in the river, making traditional transport and fishing practices, as well as water use, more challenging. It is estimated that around twenty five thousand indigenous people, from at least eighteen different ethnic groups, rely on the river in these ways.

Cacique Raoni, representing the indigenous tribes of the Xingu river opposes the Belo Monte Dam complex in the European Parliament (Flickr Source: greensefa)

The ecological impact of large dams on rivers has received a lot of investigation. The Belo Monte dam is no different and there remain large concerns regarding the potential degradation of both terrestrial and aquatic habitats as a result of the reduced flow in large sections of the Xingu River. Some flooded areas may seasonally be turned into marshland and methane production as a result of decomposition here would change the chemical balance of the water. The dam may jeopardise the ability of endangered and endemic fish species, such as the Slender Dwarf Pike Cichlid, to survive, as migration through the river system is needed for the species to reproduce. The flooding by the two-part Dos Canais Reservoir will place valuable and biodiverse forest underwater, endangering the survival of the endemic Xingu Poison Dart Frog, which is considered highly vulnerable to hydrological changes. The large reservoirs will also provide breeding grounds for the Anopheles mosquito, which may increase the likelihood of malaria; something from which the state of Pará already suffers.

Despite the hydroelectricity being created by the Belo Monte dam being renewable and produced in a carbon neutral manner, it is highly likely that it will in large part power ‘dirty’ and environmentally damaging industries. Metal smelting works and other heavy industrial plants have already began to be built on the river’s edge, utilising the hydroelectric energy being produced and cutting down swathes of forest to accommodate both the works and the new residential areas needed for their workers.

Conclusion

The Belo Monte Dam complex highlights the common conflict of interests that can lie between economic progress and environmental and social protection and narratives of opposition that continues to be raised in Brazil. As the country continues to build dams en masse in its main drainage basins, these narratives will continue to be heard but the lessons learnt from such a large scale project as the Belo Monte Dam complex may dictate how future dams are proposed and designed.

Hydroelectricity is not the only energy option open to Brazil. Proposals for wind and solar farms, that could meet twenty percent of Brazil’s energy needs by 2020, have already been met with positive responses from engineers and the Brazilian population. Energy efficiency and conservation programmes are also being used among the country’s residents, though no statutory obligation is currently being placed on industry. Many campaigners hope that with increased emphasis on energy efficiency and less on domestic generation through further dams, Brazil’s energy security and its distinctive environment will not be compromised.

References

Amazon Watch (2015) Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam: Sacrificing the Amazon and its Peoples for Dirty Energy

Global Energy Observatory (2015) List of Hydro Powerplants

Forero, J. (2013) Brazil building more dams across Amazon

World Bank Data (2013) By Country: Brazil

Key Words

Dam

A barrier that holds back water within an aquatic system, often for the purpose of hydroelectric power generation and flood control.

Hydroelectric Power

Energy that is produced by the gravitational force of water falling through a gradient for example through a turbine system in a dam.

Indigenous Population

The original inhabitants of a place.

Infrastructure

The services and facilities needed for an economy to function, for example transport networks, energy supply and health care.

Renewable Energy

The power made from energy resources that will not run out within one's lifetime.

Lesson Ideas

Imagining they are an indigenous leader like Cacique Raoni, students can put together a speech to the European Parliament highlighting, in order of importance the reasons why the Belo Monte Dam complex should not be allowed to go ahead.

In engineering teams, students can try to design a dam that takes into account the ecological needs of the Amazon basin and the tropical rainforest there. They can then present their ideas to the class and attempt to answer questions about their design.

Students can draw up a renewable energy plan for Brazil based on its climate and weather patterns. Using their own research they can see whether solar or wind energy farms are a viable alternative to the dams that the country is keen to build.