Students as partners, not just stakeholders

The idea in providing students with leadership opportunities in school is not novel. But while student leadership is more or less ubiquitous, to what extent in any given establishment does it truly hand over the reins to students themselves? Student leadership and youth empowerment has always been a core component of my approach to teaching, and I learned to recognise and move from ‘tokenism’ leadership towards ‘partnership’. Here’s my experience, which may give you some encouragement and ideas to hand over the reins yourself.

Why engage in student partnership?

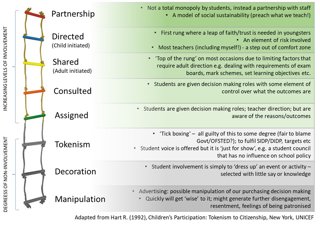

The reasons why a school, department or individual teacher may wish to engage in deeper student leadership can vary. I wanted students to not just experience leadership in learning, but also to become full partners in running the Geography Department. I came across Hart’s “Ladder of Participation”. Now it may have been published in 1992, but it is still a model which is useful today. I had started trying to increase student ownership, so I found it an exceptionally useful framework to evaluate what I was already doing. Here is an overview of Hart’s ‘Ladder’ through my interpretation.

For the purpose of this summary, I’ll focus on giving a few examples for the upper section, where student involvement is increasingly active, so is an element of trust and risk-taking.

Assigned/consulted and informed example – Year 7 Montserrat DME (Juicy Geography)

The Juicy Geography ‘Montserrat eruption role play’ activity lends itself perfectly to ‘assigned’ and ‘consulted’ levels of student leadership. Students make up crisis management teams from the Montserrat Volcano Observatory. There are three roles: an information coordinator who collects reports coming about the unfolding nature and impacts from the erupting Soufriere Hills volcano, a geologist who maps the reports and a crisis manager who uses the mapped reports to make decisions about what actions to take. They then get their decisions assessed by the Governor (more on that later). Here is the ‘assigned’ level of leadership, particularly attributed to the crisis manager. The crisis manager can be selected by the teacher or decided by each group. It is a prescribed role with set criteria where the decisions are given as a set of options. Other group members aid decision making, and the whole team are aware that the aim is to protect lives on Montserrat.

Usually the fourth role of the Governor who scores each team’s decisions and provides feedback, is done by the teacher. But to implement the ‘consulted’ level of leadership, my approach was to use 2 or 3 students who take GCSE Geography. The hardest part was finding a willing teacher to release them from whatever lesson they would have been in! In-lieu of their usual GCSE homework, they would be set a task to prepare for the Montserrat lesson by writing out a short explanation for each correct decision. This reinforces their own knowledge and understanding for their GCSE, but also allows them to provide feedback-for-learning to the Year 7s when they go get their decisions scored. They also advise the geologists on effective mapping of information.

There are bonus perks to taking these approaches. The Year 7s enjoy the presence of older students, and even though it is prescribed they have an element of control over the activity. GCSE students strengthen their geographical knowledge and understanding, while imparting some of it onto their younger peers.

Shared decisions, adult initiated – “Dragon’s Den” Decision Making Exercise

The step third from top requires adult direction, much like an instructor would do with a learner driver. Outcomes can be very variable as students have at least equal weighting in decision making.

We started the ‘Dragon’s Den’ for GCSE students in the days of lettered grades, when the OCR decision making exercise (DME) was its own exam. It was one idea of a few to attempt to raise achievement. It worked really well so it became a regularly used tool to build decision-making and analysis skills. Students were placed in teams to work on a decision-making activity, where their decisions must involve aspects that examiners will look for in an exam. One team of students are given prep-time to become Dragons (i.e. examiners), they use assessment for learning and decision-making activities in past lessons to guide them. The Dragons could be random, or selected based on their aptitude for decision-making or exam technique, and so being a Dragon is a method for them to model best practise for their peers. The teams each present their decision to the Dragons, who then give feedback based on what an examiner would look for (throwing in the “I’m in/out” for show!).

This approach proved to be popular with students, indicated by very positive feedback in student surveys and debriefs.

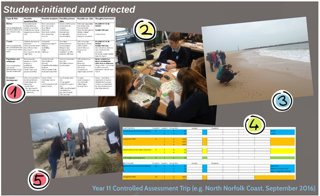

Student directed and initiated – GCSE fieldwork

This is the first rung where a leap of faith and trust is needed in youngsters. There is an element of risk involved and for most teachers (including myself), a step out of the comfort zone. Some level of adult guidance may still be necessary, especially when it comes to set requirements such as preparation for exams. In the death-throes of the controlled assessment, and further reforms on the horizon, our department took a deep breath and gave almost all control of fieldwork over the students, leaving us staff pretty much logistical support only.

Due to GCSE criteria needing to be met, guidance from staff was needed at first, ensuring that location and topic chosen meets requirements (number 1 on the image above). But after that, it was over to the students. Students chose their own objectives to investigate, while use teachers acted as consultants to help them judge whether or not they would help to answer the overall question, supplied by the exam board. Then, students researched possible primary and secondary data, including setting up their own online questionnaire (2).

The student leaders, who were to lead their peers in groups, wanted to have a pre-visit to test out fieldwork techniques in advance. This was agreed to be done on a Saturday before the full trip (3). This trip was used to refine data collection methods and complete the risk assessment.

The student leaders assigned themselves to lead data collection teams, and the other students signed up to the teams they felt would be most relevant to their chosen objectives (4). On the trip, the leaders led their peers in data collection, ensuring participation and quality (5). Our role as staff was to supervise and advise on ad-hoc basis, but leaders had to initiate.

I have to say, that field trip was both one of the best and worst experiences of my career. The latter being of my own making through anxiety and fear if something went wrong. The controlled assessment fieldwork was worth 25% of their GCSE. But I was left delighted by not just the way the student leaders conducted themselves, but also how their peers responded. Needless to say, the pride I felt in the students over the whole process is something I’ll never forget.

Student & faculty partnerships with decision making

The top rung. From the outset, I’ll state that it does not mean a total monopoly by students, put instead is a partnership with staff. On this rung, students aren’t just leaders, they are full decision makers that can inform direction and outcomes. After all, isn’t this type of engagement a model of social sustainability? We should practise what we preach (teach)!

The ‘Geography Leadership Team’ (GLT)

The ‘Geography Leadership Team’ is embedded in official department policy. This is important to avoid ‘tokenism’, as departmental policies usually are vetted and approved by the Senior Leadership Team. Here’s how it worked.

The team to manage and direct the Geography department consisted of a committee of the HOD, the teaching staff, and student leaders. The student posts lasted a year, from Easter in Year 10 to Easter in Year 11, and any student in Year 10 taking GCSE Geography could apply. We aimed for 10% of the GCSE cohort (e.g. 50 Y10 students in cohort = 5 leaders).

Responsibilities included attendance at all department meetings and events (e.g. Open Evening). Confidential and sensitive items aside, they had full input into the development and evaluation of formal processes and documents, such as the Department Improvement and Development Plan and self-assessments. They were involved in staff appointments, interviews and department reviews. Helped to develop curriculum through research, topic and lesson ideas. When choosing which of the new 9-1 specifications to follow, they had the weight of the choice after a number of meetings to make an informed decision and gather the opinion of their peers. And, of course, they represented the voices of their peers and worked to resolve issues. Quite often, a student may not have felt comfortable raising an issue to an adult, but they did to a student member of the GLT, who then brought it up in a meeting.

Evidence for outstanding practise

All of the examples I have given above were part of our successful bid to apply to the Geographical Association’s Centre of Excellence Award in 2016.

A quote from ex-student and GLT student member Eleanor Crossland was used in the application. Eleanor said that as a young person who had been involved in almost all the examples “…I would say that being trusted with the responsibility to lead an activity or even a lesson is a massive confidence boost, as well as helping to develop invaluable leadership skills for the future. One of the most important things I value in a teacher is their willingness to treat you like an adult from the age of 11, and by being asked to lead things in the classroom or taking part in decision making certainly makes me feel more like a person as opposed to a grade.” Eleanor has since graduated from St Andrews University in Edinburgh and is about to embark on teacher training. I wonder where she got the taste for that idea from!?

Things to ponder

None of the above went without a hitch, of course. But it was all part of the process and fun trying it out. There was great support from SLT, and even if things did go wrong, safeguards were in place that the worst that could happen was a deep learning experience. I left the classroom in 2017, and had these questions left to explore or ponder:

-

Which responsibilities can be totally student-owned with almost complete ‘hands-off’ from staff?

-

How to manage conflict and disruption to other responsibilities and things young people need to do? They gave up their own time to attend meetings, for example, and there are only so many homeworks-in-lieu you can give before risking interference with their studies.

-

Where should the ‘emergency brake’ be where staff step in and ‘take control’? Are more ‘breaks’ needed as you move up the latter?

-

Are any of the examples provided above simply not possible in some schools? Or are all of them possible if the right culture is fostered, and support given from management?

You are more than welcome to contact me regarding student partnership, perhaps even arrange an online consultation? Perhaps you are going for the GA SGQM/CofE – this can help! Get in touch via the ‘Contact’ page

References

-

FEHS Geography Leadership Team, Various student surveys/meeting minutes etc

-

Hart R. (1992), Children’s Participation: Tokenism to Citizenship, New York, UNICEF

-

Juicy Geography, Montserrat eruption role-play

Kit Rackley worked 13 years as a high school Geography teacher and head of department in Norwich. They maintain a blog and resource bank for educators at Geogramblings.com and is a consultant to the Geographical Association. Twitter: @Geogramblings