Dr Catherine Butler is a Senior Lecturer in the Geography Department at University of Exeter. Her research examines the processes of environmental governance, focusing on two major substantive themes - energy and low carbon transitions, and flooding and climate change adaptation. Dr Butler is Principal Investigator on the ESRC Winter Floods project.

In this interview we discuss the social and political responses to the Winter 2013/14 floods, exploring conflict and collaboration between members of the public and institutions that deliver professional help and support in the event of a flood.

Can you tell me about where, when, and how you have conducted your research into flooding in the UK?

I have conducted research looking at the social and political responses to floods in the UK over several years focused on three of the major flooding events in the last 20 years; the 2000 floods; the 2007 floods; and the 2013/14 floods. The research I have conducted has focused primarily on England and Wales. I was looking at the national picture for flood management policy following the 2000 floods, and working specifically in the areas of Sheffield, Oxford, and Gloucester following the 2007 floods, when these cities were badly affected by flooding.

Most recently, I have been researching experiences in Somerset, which was affected by severe and prolonged flooding in the winter of 2013/14. The research I have undertaken involves qualitative interviews and discussion groups with individuals directly affected by flooding and those charged with responsibilities for managing and responding to floods. I have also undertaken quantitative survey work with people that have been affected by floods, both nationally and regionally.

Who are the institutions responsible for delivering help after a flood event?

There are multiple institutions that have roles and responsibilities for delivering help after flood events and these can vary geographically, for example, in rural areas the National Farmers Union might take on more of a role in supporting farmers to recover. Key bodies involved in delivering help on the ground are: the Environment Agency, Local Authorities, insurance companies, emergency responders (police, fire, ambulance services), and non-governmental organisations or charities, such as the national flood forum.

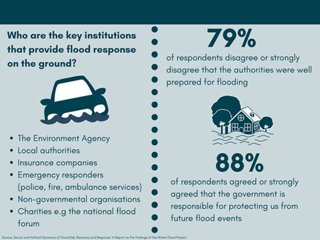

Source: Butler, C., Walker-Springett, K., Adger, W. N., Evans, L. and O’Neill, S. 2016. Social and political dynamics of flood risk, recovery and response, The University of Exeter, Exeter. Survey research undertaken in Somerset and Boston Lincolnshire after the 2013/14 floods revealed the following about perceptions of the response and responsibility for floods (Butler et al. 2016).

The primary central government department that holds responsibilities in this area is the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs but the Cabinet Office also has a role in emergency response, resilience, and planning, and several other departments have responsibilities for specific policies or initiatives. For example, the Department for Communities and Local Government delivered the flood mitigation fund – a funding stream, established following floods in 2014-15, to support household level resilience and resistance measures. Depending on the area and nature of the flooding (e.g. surface water, river flooding) there are many other organisations with responsibilities for delivering help after a flood event. These include; Internal Drainage Boards, water and sewerage companies, and Highways Authorities.

Royal Marines assist with flood defences in Somerset 2014 © Wikicommons: http://bit.ly/2raKVAp

In terms of response to flood events, how do these institutions and communities work together?

There are different forms of response to floods that relate to particular aspects of the issues throughout the various phases before, during, and after a flood. The Environment Agency, emergency responders and Local Authorities tend to give flood warnings, deal with evacuations, and initiate responses in the initial occurrence of a flood. For example, in Somerset people were evacuated by the police who were, in turn, provided with information by the Environment Agency.

The primary mechanism for recovery and repair after a flood has happened and the waters have receded is private insurance, but individual householders and volunteers also undertake repairs, clean up, and recovery activities, such as providing food and basic appliances like kettles, particularly where people do not have insurance or other kinds of support. Again, in the Somerset case, high levels of volunteers arrived from all over the UK to offer help and support to those that had been affected by flooding. This ranged from businesses donating needed items through to people supporting refuge centres.

In the longer term the Environment Agency contracts engineering firms specialising in flood defence to develop and implement flood alleviation, resistance, and resilience schemes. In some cases this involves flood defences, such as flood walls, being built but it can also involve river management options like dredging or ‘softer’ natural flood risk management techniques, such as restoring flood plains to increase water holding capacity or creating specific flood storage areas by rivers or coasts.

In addition to these types of response, there has been change over time to move toward a greater focus on individuals taking on responsibility for resistance and resilience. This more recent emphasis on individual responsibility is underpinned by notions of moving away from a context where government holds responsibility for ‘keeping the water out', to a situation where citizens are encouraged to ‘live with flood risk' (Butler and Pidgeon, 2011). In the Somerset case, those affected by flood risk not only undertook and managed repair of their own homes, including in many cases adopting household resistance and resilience measures, they also contributed to local planning and suggestions for flood defence schemes.

How have the public responded to actions taken by these institutions?

Somerset Levels 2014 © Nick, Flickr

The research I have undertaken with members of the public shows that people can often be frustrated by the responses to floods. That said, there is a clear distinction frequently made between those responding ‘on the ground’ – who are generally viewed very positively – and wider responses from government and other authorities. My research over several years in different urban and rural cases has found that people often cite feelings of isolation and abandonment, and perceive that government and other authorities are not taking enough action to manage floods in the ways they expect (Butler, 2008; Butler and Pidgeon, 2011; Butler et al. 2016). Participants in my research have frequently talked about on-going development in areas at risk of flood, as well as a lack of river and drain maintenance and long-term investment in flood defence, as things they perceive to be indicative of inaction.

Do these perceptions often cause conflict between the public and authorities after floods have happened?

Yes, I have found that conflict between different groups affected by floods has arisen after all of the flood events I have researched. This is, in part, due to perceptions of inaction or not enough action in response to flood risk. My research identifies two key issues underpinning conflict. One concerns the challenges that arise for government bodies in delivering flood risk management across the country in a constrained funding environment and with limited powers to implement change, particularly in a context where some of the needed transformations (e.g. in development practices) clash against other priorities and status quo trends (e.g. regional competitiveness, or competition in the private housing market).

Somerset levels under water 2014 © Paul Townsend, Flickr

A second related issue – linked to the limitations on powers to deliver change - concerns designated institutional responsibilities. Where members of the public have understandable expectations to be supported in protection and recovery from flood risk, these are not necessarily reflected in the statutory responsibilities of agencies and authorities. People’s expectations pertain to basic underlying rights or ideals about the role government should play in ensuring the socio-environmental conditions to live healthy lives. However, where this continues to contrast with the responsibilities and requirements on authorities, conflict is likely to emerge (see Butler et al. 2016).

So, are there more participatory ways that the public can support flood management schemes?

There are several ways in which members of the public can (and do) support, help to develop, and contribute to flood management schemes and solutions. One widely cited example of how the public can help is through participatory flood risk modelling. Here people in local areas where flood schemes are being developed are actively involved in the process of developing the flood defences. The case often highlighted is of Pickering in North Yorkshire where local community members were involved in the development of a ‘slow the flow’ natural flood management scheme (Whatmore and Landstrom, 2011).

There are, however, multiple other ways in which publics can and do become involved in developing flood management schemes and solutions. For example, in our research in Somerset residents contributed ideas for flood management schemes in their particular areas to the local authorities’ plans. Though this was ultimately successful in using local knowledge to inform development, it was also ad hoc, rather than being a more formal process like that undertaken in Pickering.

Finally, the public can contribute to flood management in quite direct ways. For example, in areas that are affected by flooding, members of the public can help to identify local issues as they arise (e.g. blocked drains) and communicate this to the appropriate body or person. In some cases communities can undertake local maintenance works. Though this is not always straight forward owing to concerns members of the public have about doing the wrong thing or being penalised for undertaking work. Many communities and people living in flood affected areas have developed flood plans for their homes and local areas so they have a clear plan for what to do when or if a flood happens.

Finally, the public can contribute to flood management in quite direct ways. For example, in areas that are affected by flooding, members of the public can help to identify local issues as they arise (e.g. blocked drains) and communicate this to the appropriate body or person. In some cases communities can undertake local maintenance works. Though this is not always straight forward owing to concerns members of the public have about doing the wrong thing or being penalised for undertaking work. Many communities and people living in flood affected areas have developed flood plans for their homes and local areas so they have a clear plan for what to do when or if a flood happens.

What have you learnt from regional case studies that could help to shape how we deal with floods nationally?

Several key insights have been possible from the regional case studies I have undertaken that could help to shape how we deal with floods nationally. Firstly, flood events present opportunities for engagement between members of the public that have been affected by flooding and decision-makers within institutions. These are moments in which new groups and networks are formed and people seek to connect with governmental organizations. Equally, they represent times when there are high levels of institutional communication and action, through public meetings and other types of formal and informal engagement. More needs to be done, however, to ensure that these opportunities are utilized to develop long-term appropriate strategies for flood risk management with the involvement of local communities.

Secondly, floods have significant negative impacts on wellbeing (e.g. see Walker-Springett et al. 2017; Butler et al. 2016) and conventional approaches to assessment and measurement pertaining to policy responses limit abilities to take account of these and to effectively respond. Given this, social and community resilience may be underestimated in terms of its role in enabling people to cope and recover from floods, and in mitigating negative implications for wellbeing. Greater support could be given to mechanisms and policies that aim to enhance social and community forms of resilience. Specific recommendations arising from my research include the importance of increasing the use of professionalised community coordinator roles that can form a link and source of two-way exchange between agencies, responders, governing bodies, and communities. Individuals working in community support roles provide an important mechanism during emergency and post-flood contexts but also have roles in generating community resilience outside of these times. There is a role for institutions in ensuring social and material infrastructures are in place that can effectively support the emergence and maintenance of social resilience. Building social and physical resilience to floods requires support, investment, and strategic planning in order to make it an integral part of flood risk management. For it to be successful it needs to go hand in hand with other important aspects of flood risk reduction that are beyond the control of local communities, such as land use planning and development.

Finally, emergency funds and their allocation at times of intense pressure and stress following floods can contribute toward short-term decision-making and a lack of strategic direction. Processes for allocating funding at these times should be better formalised so that communities, local authorities, and agencies can know with greater clarity what opportunities are available for additional funding allocations following major events. This is to recognise that severe floods are likely to happen more frequently and enable a greater degree of strategic oversight in the decision-making and funding allocations that are made. Additionally, consideration should be given as to how government initiatives (such as the flood mitigation fund) could work in concert with insurance industry protocols, for example, loss adjusters assessing for property level resilience and resistance measures as part of the insurance claims processes. This is beginning to happen following floods in 2014 and 2015 but it is important to maintain momentum and ensure the processes continue to be developed.

Finally, emergency funds and their allocation at times of intense pressure and stress following floods can contribute toward short-term decision-making and a lack of strategic direction. Processes for allocating funding at these times should be better formalised so that communities, local authorities, and agencies can know with greater clarity what opportunities are available for additional funding allocations following major events. This is to recognise that severe floods are likely to happen more frequently and enable a greater degree of strategic oversight in the decision-making and funding allocations that are made. Additionally, consideration should be given as to how government initiatives (such as the flood mitigation fund) could work in concert with insurance industry protocols, for example, loss adjusters assessing for property level resilience and resistance measures as part of the insurance claims processes. This is beginning to happen following floods in 2014 and 2015 but it is important to maintain momentum and ensure the processes continue to be developed.

Overall, the research I have undertaken in different regional contexts highlights the importance of preparing for dialogue between communities and stakeholders, consistently shows the negative impacts of floods on people’s wellbeing, and suggests a need to embed more strategic processes for decision-making about funding and resilient rebuilding in post-flood contexts.

What do you feel will be the key issues facing decision makers dealing with future flood events?

The key issues facing decision makers in future are likely to be in developing responses that can take into account the increases in severity and frequency of floods that are projected with climate change. Key to this is ensuring more consistency across different parts of the UK in terms of developing long-term responses to floods, as well as developing better support systems for people affected by floods with a view to reducing impacts on wellbeing and mental health.

At present, there are some good examples of long-term thinking and strategic approaches to managing floods risk, such as the Thames 100 project (HR Wallingford, 2017), but this type of response is relatively piecemeal across the UK. A key challenge is always funding, so ensuring that long-term thinking is built into the responses that happen in the immediate aftermath of floods is likely to be important. Large sums of money both private (e.g. through insurance payments) and public (e.g. through government emergency funds) are spent in the repair and recovery process after floods but much of this supports ‘return to normal’ works, rather than being utilised to develop more transformative responses that embed longer-term resistance and resilience to floods.

The evidence from studies of flood response and recovery overwhelming show the negative impacts of flooding on people’s health and wellbeing. This has been shown across different age groups, demographic factors, and economic positions (Butler et al. 2016; Walker-Springett et al. 2017). Developing support systems that can help to address the wellbeing and mental health impacts of floods are therefore likely to be increasingly important in future.

Lesson ideas

For more illustration and introduction to the case study show the video ‘Somerset battles extreme flooding’(Channel 4 News, 2014)

Ask pupils to describe the situation: what sort of damage has occurred as a result of flooding? Perhaps pupils have experienced flooding themselves; ask them to consider: who do they feel should be providing help to those affected by flooding? Reflect on the local, regional and national scale.

Download the document ‘Ask the Expert Social and Political Responses to Flooding Activity’. This worksheet contains interview excerpts from those affected by flooding, and those who help manage flood response in a professional capacity. Ask pupils to complete the task and discuss their responses as a class.

Key words

Resilience

The ability of societies and environments to adapt, react dynamically, and maintain their existing functions or be quickly restored to their previous or an improved state before a flooding event

Participatory flood risk modelling

Stakeholders and public working together beyond consultation to co-produce flood risk models to support understanding of how to manage future flooding scenarios

Stakeholder

In this research, stakeholder refers to those working in a professional role in managing flood risk

Public

In this research, public refers to those who have experienced disruption from flood events in their daily lives

Links

Dr Catherine Butler, personal page

National Flood Resilience Review

Department for environment food and rural affairs

Department for communities and local government

News

Flooding victims frustrated with government support, The Exeter Daily (2016)

Somerset floods: The Moorland villagers 'staying put', BBC (2014)

10 key moments of the UK winter storms, BBC (2014)

Flooding: UK plans for more extreme rainfall, The Guardian (2016)

Further reading

Butler, C., Walker-Springett, K., Adger, W. N., Evans, L. & O'Neill, S. 2016. Social and political dynamics of flood risk, recovery and reponse. Exeter: University of Exeter.

Butler, C. and Pidgeon, N. 2011. From ‘Flood Defence’ to ‘Flood Risk Management’: exploring governance responsibility and blame, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29: 533 – 547

Butler, C. 2008. Risk and the Future: floods in a changing climate, Contemporary Social Science: Journal of the Academy of Social Sciences, 3(2): 159-171

HR Wallingford (2017) Thames 100 Project

Tapsell, S. M., Penning-Rowsell, E. C., Tunstall, S. M. & Wilson, T. L. 2002. Vulnerability to flooding: health and social dimensions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series a-Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences, 360, 1511-1525.

Walker-Springett, K., Butler, C. & Adger, W. N. 2017. Wellbeing in the aftermath of floods. Health & Place, 43, 66-74.

Whatmore, S. J. and Landstrom, C. (2011) Flood Apprentices: An exercise in making things public, Economy and Society, 40(4): 582-610

This resource was kindly supported by the University of Exeter